COVID-19 Outlook: Regaining Our Footing with Continued Optimism

This week, our COVID-Lab forecasting model continues to show reassuring trends of declining COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations throughout the country. Here are more details from our weekly modeling update:

- Nationwide, the average PCR test positivity rate dropped again this week to 8.6%, down from 10% last week.

- Case incidence is decreasing alongside the declines in positivity rates—substantially in many places. In fact, this week, 40% of the counties we monitor in our model have dropped below 200 weekly cases per 100,000 individuals. This includes large counties like Kings County (Seattle), Wash. (78 per 100k), Wayne County (Detroit), Mich. (82 per 100k), San Francisco County, Calif. (108 per 100k), and Philadelphia County, Pa. (142 per 100k).

- Counties throughout Florida continue to experience a decline in PCR test positivity and case incidence, and our models project further improvement in the coming weeks in these areas. This is encouraging news, given recent reports of an increase in the proportion of cases in Florida with the B.1.1.7 variant, first identified in the United Kingdom. As of now, it does not appear that the presence of this variant is resulting in increasing case burden.

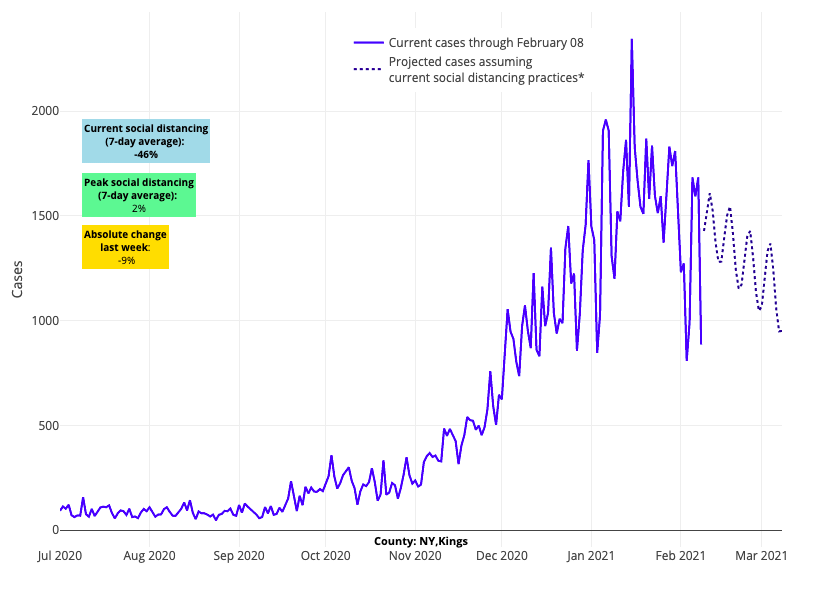

- We are also seeing cases decrease in areas that previously were showing persistent increases. This includes the New York City boroughs, which are all now projected to see decreases in case incidence in the coming weeks. While overall case burden remains high (between 300-400 weekly cases per 100,000 individuals) in these areas, our models, which also incorporate wider regional effects, forecast cases will continue to decline.

Above are the projections for Kings County (Brooklyn) in New York.

Amidst this optimism, there are still some areas of concern:

- While trends are improving, a number of larger counties still have very high weekly case incidence and should be cautious as they continue to reopen. This includes Bexar County (San Antonio), Texas (610 per 100k), Tulsa County, Okla. (460 per 100k), and Miami-Dade County, Fla. (425 per 100k).

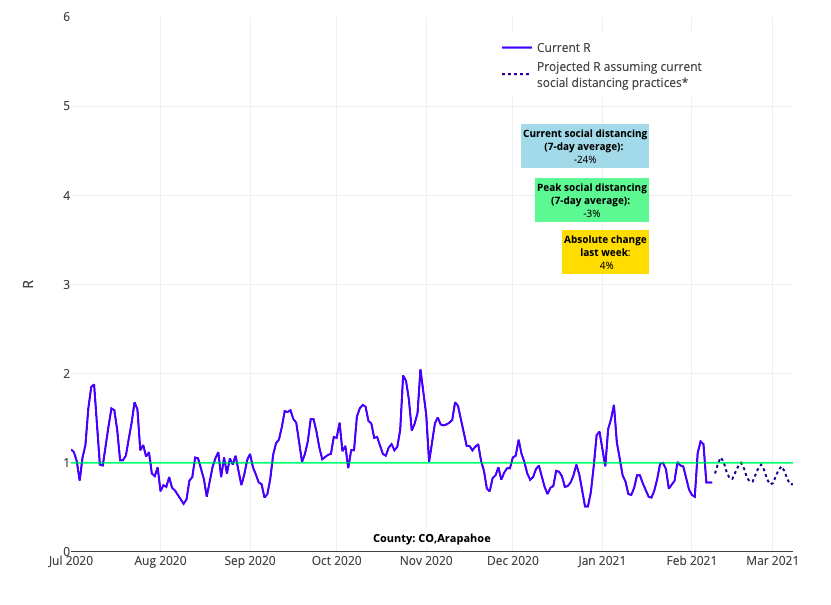

- In Colorado, after weeks of declining cases in many counties, reproduction numbers (a measure of transmission rates) have now begun to creep back up toward 1, particularly in areas surrounding Denver and Boulder. This bears watching in the coming weeks.

Above is the reproduction number projections graph for Arapahoe County in Colorado.

- One of the few large metropolitan counties that continues to demonstrate high reproduction numbers is Clayton County outside of Atlanta, home to Hartsfield International Airport. Our models project a decline in cases for this county over the next four weeks, but the high transmission rates will need to be carefully watched.

It is important to note that the decline in case incidence we are observing is happening simultaneously across nearly all of the counties that we follow. In previous periods of this pandemic, it was more typical that one region of the country would see increasing case numbers as other areas were on the decline. For example, as cases declined in the Northeast in late spring of 2020, the Southeast and Southwest were beginning to surge. Or in the early fall of 2020, the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast were just beginning their second wave while the Midwest and Mountain States were well into their fall surge. This occurred as other locations, such as New England, were experiencing a decline in transmission.

Over the next few weeks, we will be watching case incidence very closely across all of the 819 counties we monitor to assess for signals of increased transmission that might reflect accelerated transmission of variant strains. We will also be observing whether larger numbers of gatherings associated with the Super Bowl might have conferred new risk to some regions (particularly in Boston, Tampa Bay and Kansas City).

With Variants Present, Why Are Cases Falling So Quickly Across the Country?

Many may be confused about why we continue to see falling trends in case incidence and hospitalizations given increasing reports of variant strains that are potentially more easily transmissible. As we noted last week, transmissibility—or the contagiousness of the virus—is a complex process not limited to intrinsic changes to the virus, but inclusive of many environmental and behavioral factors. It is still way too early to predict whether these variants will or will not cause a late spring surge. Thus far, we have not yet seen any signals of accelerated transmission despite the presence of these strains in the U.S. for some time now.

One possibility for the continued decline in case incidence in most regions is that the number of people across our population who have already been infected or have received a vaccine has reduced the number of individuals susceptible to infection, or at least severe infection. As the number of susceptible individuals in a community is reduced, the ability of the virus to transmit will also be reduced.

While the spread of novel variants has the potential to overcome this protection from prior infection or vaccination, the vaccines being administered in the U.S. appear to be effective at protecting against the UK variant. And we have detected far fewer cases nationwide of the other concerning variant strains. Even if other variants appear, it is likely that an immune response produced after infection from an earlier strain of the virus or after vaccination will provide at least some level of protection.

Ultimately, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this balance between population immunity from prior infection and continued vaccination and the evolution of novel strains will lead to endemic presence of SARS-CoV-2, similar to seasonal influenza. When a virus becomes endemic, it is part of the predictable landscape of seasonal viruses. The 2009 pandemic influenza strain is a great example of how a pandemic strain of virus became just another one of the strains of seasonal influenza viruses we see many winters. At this endemic state, we would not expect more surges of case incidence, but rather persistent seasonal increases in cases and transmission rates. Further, we would hope that infections experienced during this endemic period would be milder and not require hospitalization at the rates we saw this past year. A recent article from The Washington Post discusses this concept well.

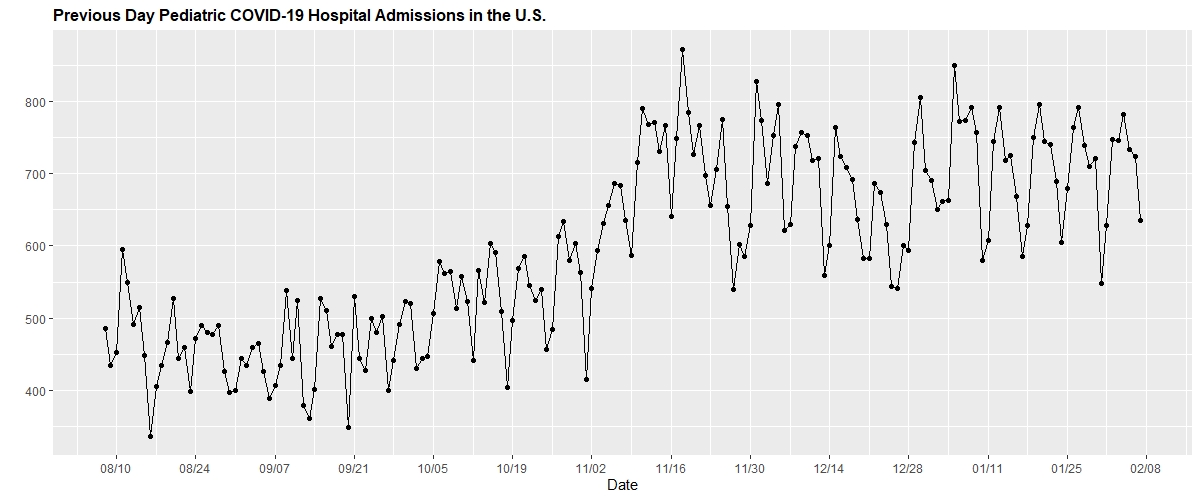

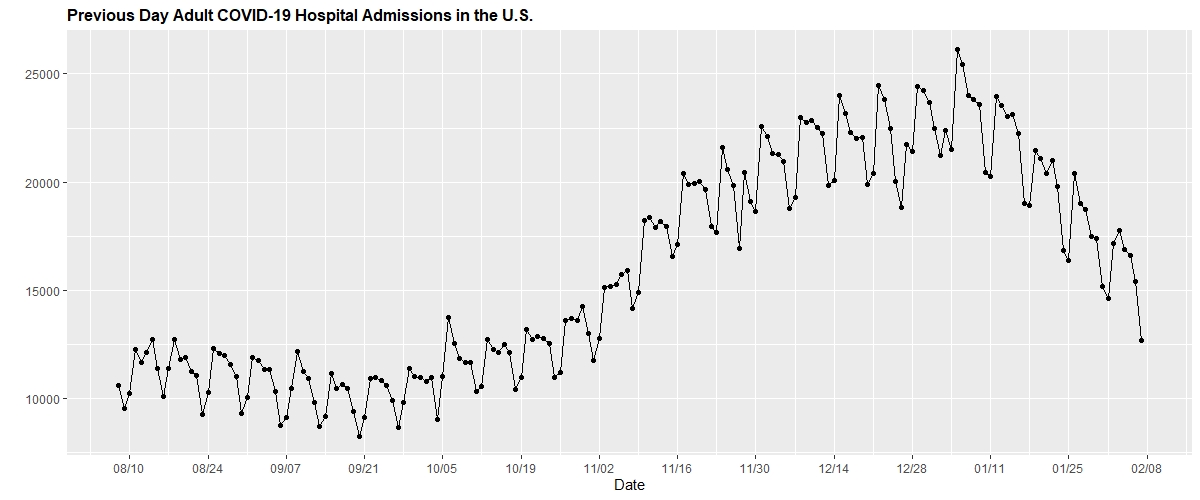

An Update on Pediatric Hospitalizations

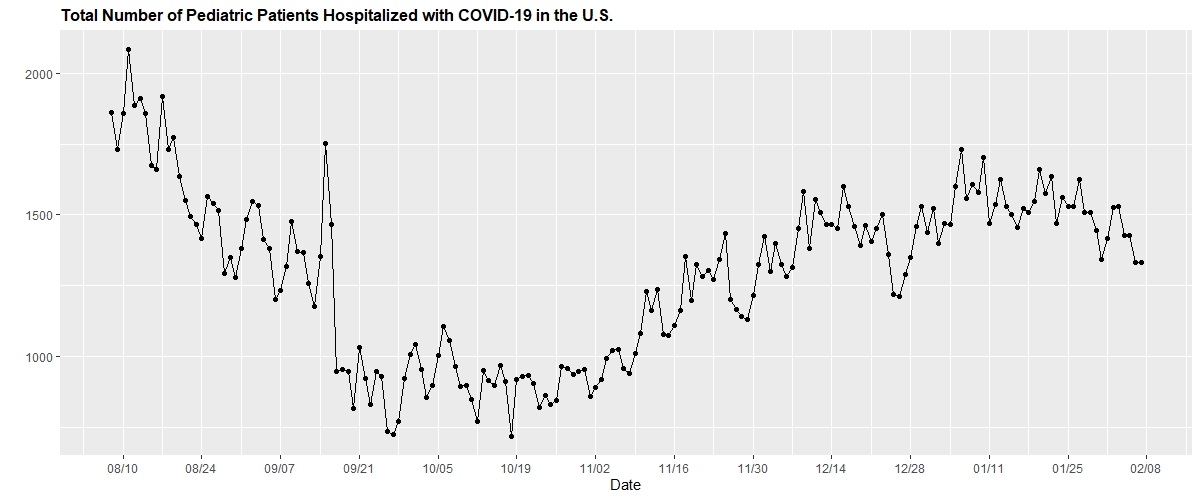

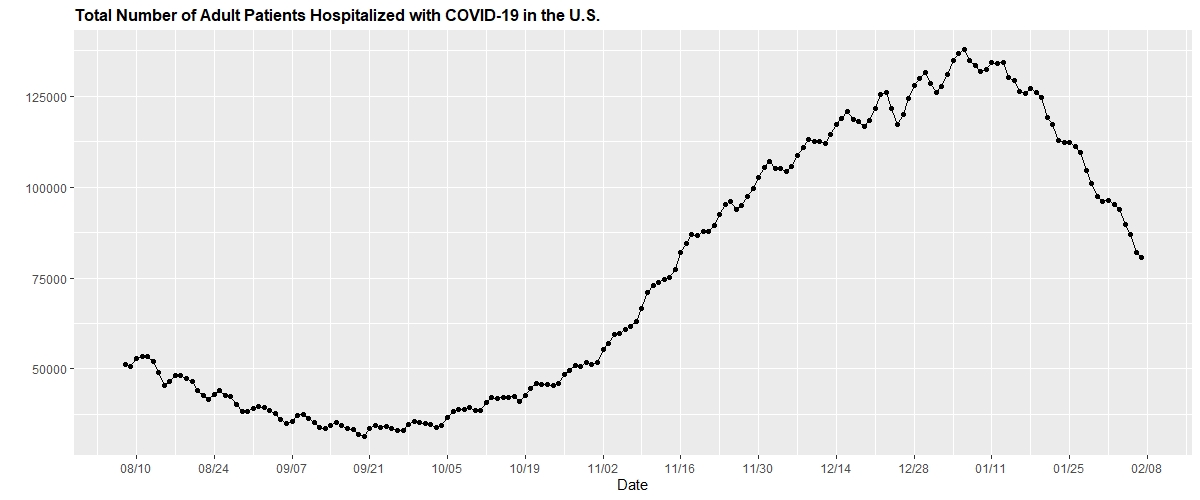

A somewhat unusual finding in the data this week is the lagging improvement in pediatric hospitalizations compared to adult hospitalizations. At least 19 states are seeing peak or increasing hospitalizations of youth with COVID-19, even as adult hospitalizations decline in all states. This may be because a small subset of children have required hospitalization and care for an inflammatory immune response, known as MIS-C syndrome (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children), that happens well after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection. Modest increases in MIS-C syndrome hospitalizations have been noted at a number of children’s hospitals in recent weeks. Because MIS-C represents an immune response to prior infection, it is no surprise that these hospitalizations lag behind the peaks in case incidence.

However, pediatric admissions remain quite low overall; daily hospital census only approaches 15 per 1 million children (see graphs below provided by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services).

We will continue to report on these trends, and we encourage those conducting genomic surveillance that seeks to identify the prevalence of variant strains in adults to also extend these efforts to children.

Still, Getting Youth Back in the Classroom Remains the Priority

As we continue to see a decline in case incidence across the country, we believe that schools should move forward with returning more children to the classroom. However, we are advising schools to be measured in their approach during the final weeks of winter; a common refrain among our team, given the uncertainties that still remain, is to “walk before you run.” This means that each step to return more children to the classroom should be diligent, incremental and monitored closely. With each step, students and staff must maintain their commitment to the multilayered safety plans in place in each school and avoid the temptation to loosen restrictions just because the “numbers are down.”

As school districts progress to more in-school learning, we know great anxiety remains among school communities and staff. In particular, there are concerns about ventilation in classrooms and the speed at which school employees are being vaccinated. To the first point, we would emphasize that improvements to ventilation can be helpful, but are not among the most important interventions needed to reduce transmission risk within schools, which include masking, distancing, hygiene and reducing the number of contagious individuals in the building (see our policy review for more on the evidence behind individual mitigation strategies).

We also are thrilled that some school staff in the region have begun to receive vaccinations (in Philadelphia, 121,000 have received their first dose and more than 50,000 have received their second dose), and the City of Philadelphia announced this week that Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia personnel will be administering the vaccine to teachers, principals and staff at all schools in Philadelphia in the coming weeks. However, vaccination of all employees should not be viewed as a precondition for safely returning children to school. We now have ample evidence this can be done safely in the interim, particularly as case incidence falls throughout a region.

Assurance testing, or regular (weekly) testing of asymptomatic individuals, can provide an extra degree of security to school communities, particularly while staff are in varying stages of vaccination. We’re proud to report that through Project: ACE-IT, the southeastern Pennsylvania testing initiative PolicyLab partners on with local public health departments and school leaders, 42 school districts in our region are now implementing an assurance testing program, with the potential for 224 public, parochial, charter, and private schools for children with special educational needs to be up and running by the end of February.

We are most excited about the impact of this program on the reopening plans of the School District of Philadelphia, which has already paved the way for children with special needs to return to in-person assessments and services and is anticipating the return of elementary school students to classrooms before the end of the month. With the low density of students expected upon return, the district will be able to maintain 6-foot distancing and, together with masking and screening, protect students and staff alike. The assurance testing program will provide additional important data points regarding the presence of asymptomatic cases in schools; we are hopeful that Philadelphia will see the same infrequency of infection that New York City saw when their schools reopened.

With declining case incidence nationwide, vaccine distribution picking up, assurance testing becoming more prevalent, and warmer weather in our near future, our optimism is growing for a brighter spring.

Jeffrey Gerber, MD, PhD, MSCE, is the associate director for inpatient research activities for Clinical Futures at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is a co-author of PolicyLab’s Policy Review: Evidence and Guidance for In-person Schooling during the COVID-19 Pandemic.