Understanding Juvenile Justice through a Health System Lens

Think back to your teenage years. If you’re like most people, it was probably a period of rapid change—not only physically, but also cognitively and emotionally. From a developmental perspective, teens and young adults are more likely to be impulsive and susceptible to negative peer influences, and they’re less apt to weigh the long-term consequences of their actions.

Because youth are developmentally different from adults, the juvenile justice system was historically designed to be rehabilitative and restorative, rather than retributive. Despite this stated goal, over the last several decades, children have been subjected to many of the same harsh, punitive policies imposed in the adult criminal justice system.

Last month, at PolicyLab’s “Charting New Frontiers in Children’s Health Policy and Practice” forum, the Stoneleigh Foundation hosted a panel session on “Transforming Juvenile Justice to Improve Youth Outcomes in Philadelphia.” With so many children’s health researchers, practitioners and policymakers in attendance, we thought it important to call attention to the parallels between the juvenile justice and health services systems.

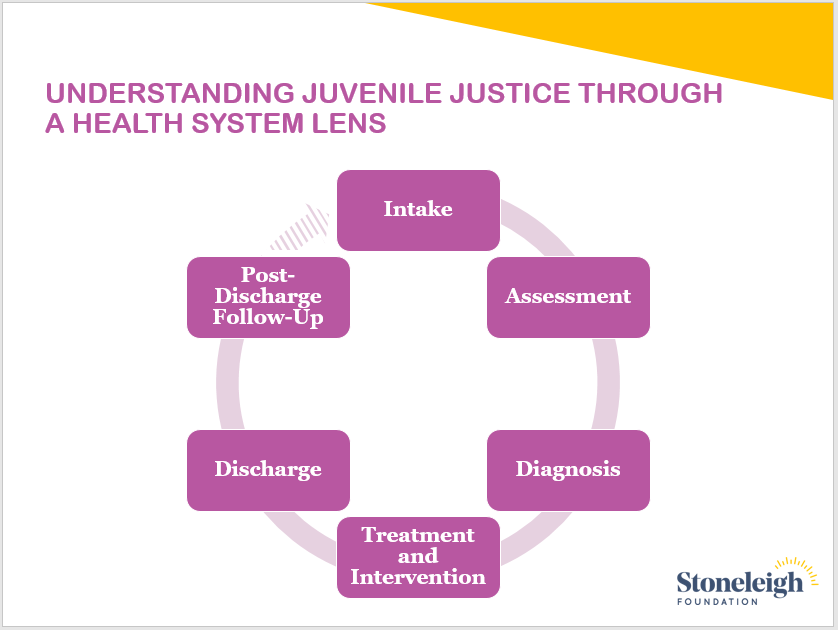

In juvenile justice, “arrest, charging and adjudication” serve as analogues to the health system’s “intake, assessment and diagnosis.” The justice system has various mechanisms for “treatment and intervention,” which range from minimally invasive to aggressive, depending on the nature of the charge. Following formal “discharge” from the system, a young person can either remain rehabilitated or—as we see all too often—reenter, initiating the cycle once again (Figure 1).

Stoneleigh’s panel discussion featured four individuals working at the leading edge of juvenile justice innovation in Philadelphia. In their remarks, Kevin Bethel, Bob Listenbee, Dr. Naomi Goldstein and Timene Farlow each highlighted how interventions at key stages of system-involvement can significantly affect outcomes for our young people.

Here are a few key takeaways:

- Kevin Bethel, a Stoneleigh Fellow and 29-year veteran of the Philadelphia Police Department, talked about the impact of the Philadelphia Police School Diversion Program, a police-led initiative that diverts students who commit first-time, low-level delinquent acts from arrest and instead provides them with free intensive support services. The program eliminates the traumatic experience of an arrest while helping to address the root causes of a young person’s behavior. Since its launch in 2014, roughly 1,000 fewer kids are arrested each year in Philadelphia schools.

- Bob Listenbee, a former Stoneleigh Visiting Fellow who currently serves as first assistant district attorney at the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office, noted that the vast majority of justice-involved youth are in the system because of minor offenses, and many remain for too long while their underlying needs go unaddressed. Before proceeding to formal adjudication, many cases involving youth should be considered for diversion, and young people should be referred to appropriate support services. Cities can then reinvest the resources saved from incarcerating youth into prevention efforts and school- and community-based supports.

- Dr. Naomi Goldstein, a Stoneleigh Fellow and director of Drexel University’s Juvenile Justice Research and Reform Lab, discussed her collaborative effort with the Philadelphia Juvenile Probation Department to implement a “Graduated Response” approach to juvenile probation case management in the city. In most jurisdictions, youth on probation must comply with multiple, long-term conditions that are not compatible with their stage of development. Failure to do so often results in placement at a distant, out-of-home juvenile justice facility. The Graduated Response approach restructures juvenile probation to be more aligned with adolescent development and uses short-term positive reinforcements, incentives, constructive feedback and sanctions to encourage youth to fulfill their probation terms.

- Timene Farlow, deputy commissioner of the Juvenile Justice Services Division at the Department of Human Services, oversees Philadelphia’s Juvenile Justice Services Center (JJSC), the city’s only secure detention center for youth. For many young people who enter secure detention, earlier interventions have not been effective—but it’s not too late. The JJSC has services, practices and strategies in place to meet the needs of the youth in its care and help prevent their deeper penetration into the system. Available resources at the JJSC include a trauma-trained staff, a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist, 24-hour nursing care and an in-house school with credit-bearing courses and strong alignment with the School District of Philadelphia’s curriculum.

The good news is that, despite the many challenges we face, leaders in Philadelphia are finding new, effective and developmentally sound ways to meet the needs of young people before and during their involvement with the juvenile justice system.

So what role can the children’s health community play?

- Connect youth with positive activities, influencers and experiences

- Equip youth with tools to cope with the challenges they face in their families, schools and communities

- Identify local programming and refer youth and their families to wraparound prevention and supportive services

- Develop evidence-based programs and models that meet the specific needs of youth

Understanding the parallels between our juvenile justice and health systems—and the ways these systems impact and influence each other—is critical to strengthening outcomes for some of our most vulnerable young people. We hope this discussion is just the start of a fruitful and transformative collaboration between our fields.

Marie N. Williams, Esq., is a senior program officer at the Stoneleigh Foundation and moderated the “Transforming Juvenile Justice to Improve Youth Outcomes in Philadelphia” panel during PolicyLab’s 10th anniversary forum.