Preserving the Children’s Health Insurance Program: A No-Brainer to Protect Children in Working Families

As a pediatrician, I have a front-row seat to how health insurance impacts the well-being of children. Nearly half the patients I see are covered by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), both of which have comprehensive sets of benefits and are historically thought of as safety nets for the unemployed. However, you might be surprised to learn that the fastest growing users of these public health insurance programs for their children are employed and unable to afford or receive health insurance for their children through their employer health plans.

New PolicyLab Study Shows Importance of CHIP, Medicaid to Working Families

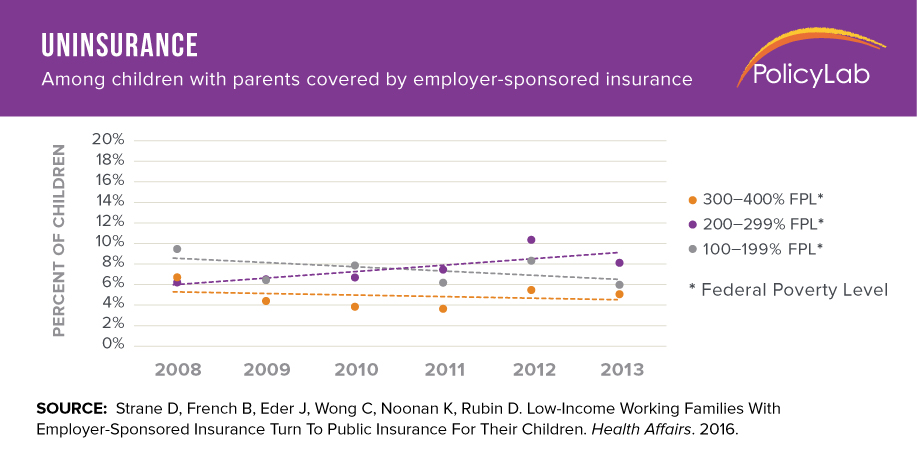

To learn about this recent trend, our team at PolicyLab used survey data from 2008-2013 to understand the health insurance decisions working parents were making on behalf of their children. What we found is that low- and moderate-income families between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level ($23,550-$94,200 for a family of four), whose parents were receiving insurance through their employer, increasingly looked to Medicaid or CHIP to insure their children.

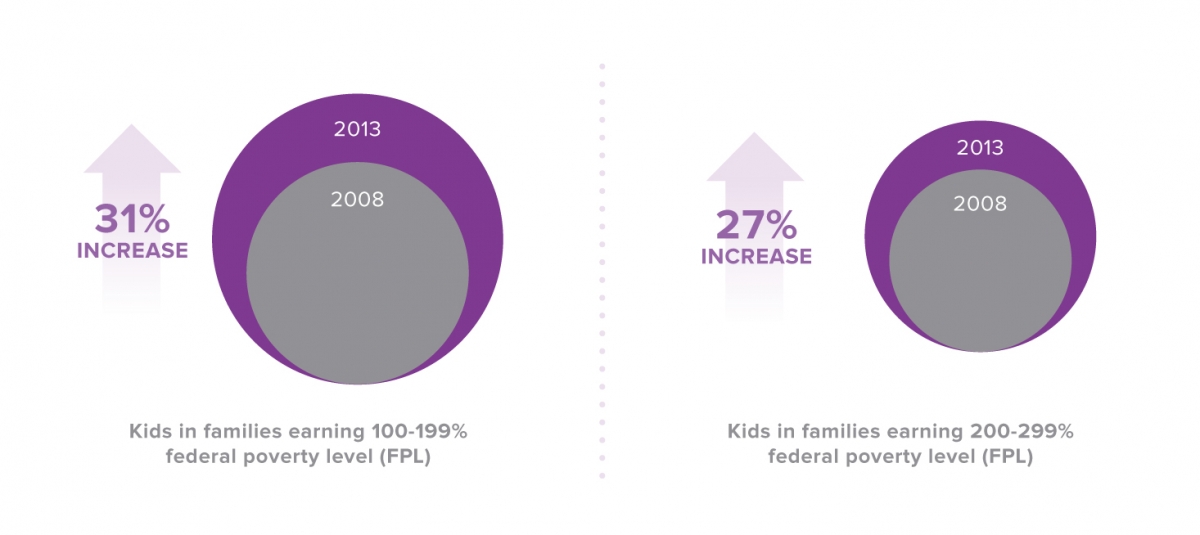

By 2013, the proportion of such families electing to cover their children through CHIP or Medicaid increased by 20 percent overall, and by more than 30 percent among families with household incomes between 100 percent and 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or up to $47,000 a year for a family of four. By 2013, one-third of working families in that income bracket were relying on CHIP and Medicaid to extend coverage to their children. These findings, published today in the December issue of Health Affairs, show just how important CHIP and Medicaid have become for working families.

A Changing Health Insurance Landscape

Some might question why families increasingly made the decision to move their children’s coverage off of an employer-based plan, and whether they should have been permitted to do so. Simply put, families were responding rationally to rapidly changing financial pressures.

As employers faced the rising cost of premiums to insure their workers’ families (which increased by 41 percent to $17,000/year between 2008 and 2015), a cost that far exceeded that of providing single coverage (which reached $6,000 by 2015), their offerings began to change. Some employers began to drop dependent coverage from their available insurance plans, if they even offered insurance to their employees at all. Other employers increased costs that workers must contribute toward family plans, whether by increasing the premium they needed to pay, by increasing out-of-pocket deductibles they could expect to pay if their children got sick or by restricting the providers their children could see.

Employees faced a dilemma: insure yourself for less money, or choose a plan that was either unaffordable or did not provide complete health benefits to your children. For many, the cost to cover their children became prohibitive: annual worker contributions to family premiums rose from $3,400 in 2008 to $4,700 in 2015. Deductibles also became more common, with the average deductible for an employer-based family plan rising from less than $800 in 2008 to more than $2,000 by 2015. What’s more, many employer-based plans did not offer reimbursement for vision, dental or mental health providers, which are commonly included in public insurance programs for children.

As lower-income families experienced these changes, CHIP and Medicaid (if their children were eligible within their state) may have been the only affordable option if they wanted to continue insuring their children.

By 2016, 35 million children in the United States were covered by Medicaid or CHIP, contributing to the nearly universal rate of children’s health insurance coverage in this country.

By 2016, 35 million children in the United States were covered by Medicaid or CHIP, contributing to the nearly universal rate of children’s health insurance coverage in this country. However, CHIP funding is set to expire in September 2017 if Congress does not act to renew it.

The Limitations of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to Help These Families

The arrival of the ACA in 2011, and the emergence of the health insurance exchanges by 2014, provided new options for parents to obtain subsidized coverage for themselves and their children if they could not receive insurance through work, or if employer coverage was unaffordable. Yet, like employer plans, exchange plans were often not promising for working families. Deductibles remained high, and they overwhelmingly lacked the comprehensive benefits that CHIP and Medicaid offer for children. Other parents were also unable (through a “family glitch” in the ACA legislation) to receive tax subsidies to enroll their children in the exchanges because the test for affordability only considered the cost of individual coverage, not family coverage that is much more expensive. Therefore, CHIP and Medicaid became the backstops for children in working families during this time, and will remain important if the ACA is not improved or replaced with law that provides better options for working families to cover their children.

The Future of Children’s Health Care Coverage

So, where does this leave us for protecting the nearly universal nationwide coverage we’ve achieved for children over the last 20 years? On the heels of this study, and with the change in our national direction following Election Day, many working families will rely entirely on Medicaid and CHIP to provide cost-effective and comprehensive coverage for their children. The maintenance and protection of these programs is now more important than ever.

One need only look at a secondary finding in our study that serves as a bellwether warning for what might happen if Congress does not renew funding for CHIP before it runs out in September 2017. For working families between 200 percent and 300 percent of federal poverty level ($47,100-$70,650 for a family of four), who were not offered or could not afford dependent coverage for their children through their employer, we detected a 53 percent rise in uninsurance for their children. This was likely due to more restrictive eligibility levels for Medicaid and CHIP in their states, which left them with no affordable options and nowhere to turn for help. Families in those states were asked to make the difficult decision to uninsure their children and hope for the best.

One need only look at a secondary finding in our study that serves as a bellwether warning for what might happen if Congress does not renew funding for CHIP before it runs out in September 2017. For working families between 200 percent and 300 percent of federal poverty level ($47,100-$70,650 for a family of four), who were not offered or could not afford dependent coverage for their children through their employer, we detected a 53 percent rise in uninsurance for their children. This was likely due to more restrictive eligibility levels for Medicaid and CHIP in their states, which left them with no affordable options and nowhere to turn for help. Families in those states were asked to make the difficult decision to uninsure their children and hope for the best.

If Congress fails to re-fund CHIP next year, we will see this difficult decision play out for families all across the country in numbers we’ve never seen before. Protecting CHIP is now a no-brainer for the future health of our nation’s children.