COVID-19 Outlook: Running Out of Time, And Out of Patience

As we quickly move toward the end of summer, this week’s four-week projections have us convinced that this Labor Day will be far different than years past.

Last week, we noted with some optimism that increasing commitments from state governors to reduce gathering sizes, limit access to bars, and adopt masking standards were leading to noticeable improvements in our forecasts, including in Louisiana, Alabama, some areas of Mississippi, Arizona, and Colorado.

This week, our optimism is waning.

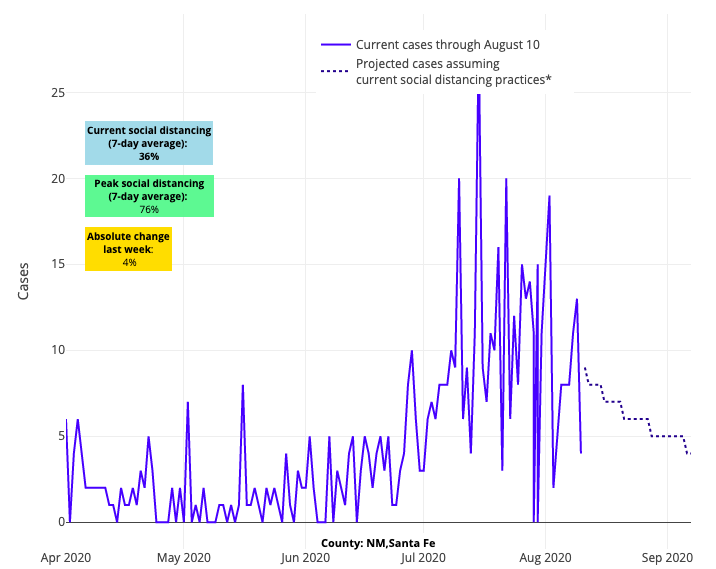

Sure, there are areas that continue to have improved forecasts in our models. Certainly, Arizona tops the list as a clear example that the sensible, consistent masking requirements and distancing restrictions proposed by the White House Coronavirus Task Force can have broad impact in a region. New Mexico, which often gets less attention, started its restrictions earlier and has largely avoided the big wave that swept across the south this summer.

Above are the projections for Santa Fe County in New Mexico.

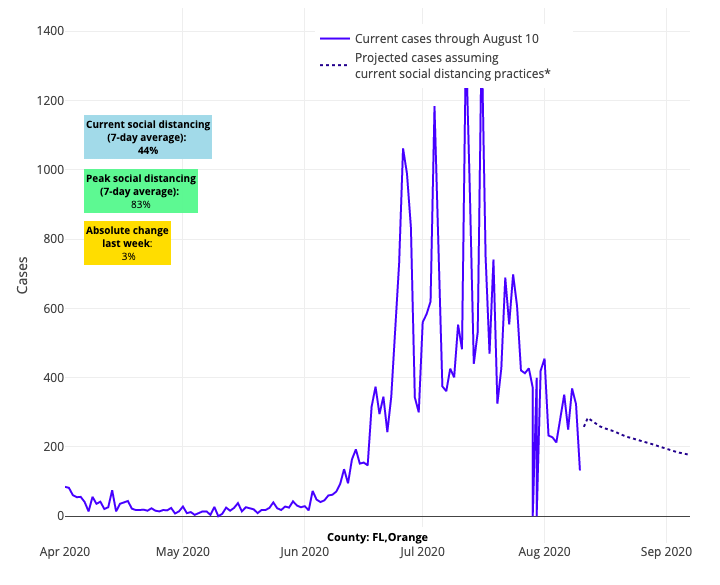

Some may point to Florida’s improvements to tout that limited state restrictions can still work, but we believe their improving projections are more likely the result of strong city and county mandates that have reached sufficient numbers. Take Orlando for example, which has led the way with a sustained universal masking requirement that is helping to degrade case counts, even with the reopening of Disney World and the arrival of the NBA. Their residents have accepted strong tradeoffs in order to reopen important parts of their economy. New York and Michigan continue to shine in our forecasts, as does Colorado.

Above are the projections for Orange County in Florida.

But beyond these successes, there are many troubling signs in the data this week.

The most important signal we are detecting is that risk is continuing to shift from the south to north at the worst time, creating a potential perfect storm in advance of fall and cooling weather. From Seattle to Minneapolis to Chicago to Boston, we are seeing transmission risk continue to gain strength in our forecasts. Along the I-95 corridor between Virginia and New Jersey, we have not seen evidence of improvement. In the Midwest and across the Heartland, some cautious optimism of improving trends in the last couple of weeks has largely stalled, and we are seeing transmission risk rise in areas of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Nebraska, Missouri and Oklahoma.

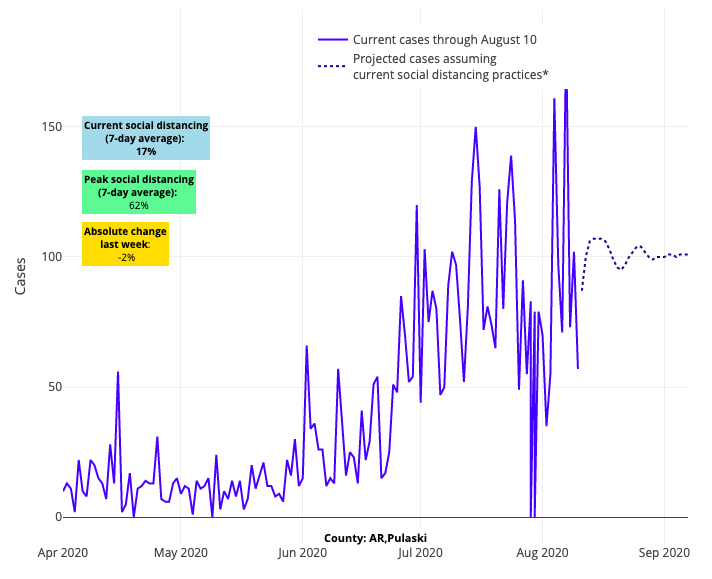

Many of the usual actors that have been problematic throughout the summer continue to have poor predictions in our model. Some areas of California are slowly worsening, and even those counties that have abated a bit are going to take weeks to improve. The Carolinas, Georgia and Tennessee continue to plod along with high disease burden, and progress in Little Rock, Ark. appears to have stalled, suggesting that masking mandates alone only work with sustained commitment by residents to adopt the requirements and law enforcement to ensure that restrictions are being followed.

Above are the projections for Pulaski County in Arkansas.

This disconnect between emerging state restrictions and enforcement is perhaps what is most frustrating and worrisome. The malalignment is so endemic across many states that it erodes confidence that the Task Force recommendations, even if adopted by governors, can have sustained impact. For example:

- Bars have opened in Texas in defiance of state orders, and predictably the risk has quickly worsened again in Dallas, Houston and Austin.

- Maryland and Virginia may have some sensible restrictions on the books, but if you look past the window dressing, you’ll see the cracks in their strategy. Maryland has restrictions in place related to capacity and social distancing, but there is no specific limit on gathering sizes and most businesses are open. And while restrictions were reinstated in the Hampton Roads region near Virginia Beach, on the whole most businesses in Virginia are open, including gyms at 75% capacity.

- Wisconsin, a state that has historically led the way in public health, is facing a crisis of leadership and governance. Theoretically, Governor Evers has adopted a statewide masking mandate, but it has no enforcement mechanism. Following a court overturning the governor’s stay-at-home order early in the pandemic, there have been few statewide restrictions enacted, including none on gathering sizes. It’s no wonder why the Green Bay and Milwaukee areas are surging, and Madison continues to struggle as students return to the University of Wisconsin.

Our governments’ ability, both federal and state, to serve the people has been tested throughout this crisis, and it is hard not to feel like it is cracking.

This brings us to our own predictions for fall, which are becoming more confident by the day. After six months of observing outbreaks in nursing homes, prisons, congregate living facilities for meatpacking plants, and now restaurants and bars, we know just how easily this virus can spread in crowded environments. And our own work published this summer revealed that summer transmission may pale in comparison to the transmission rates and higher viral inoculums we could see in colder weather—especially if we do not sustain a commitment to sensible distancing and masking in our daily lives.

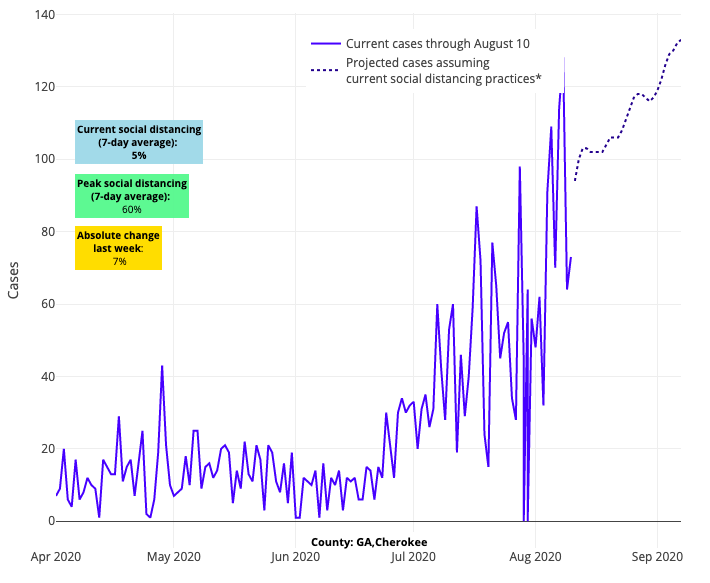

It is because of these assumptions that we are concerned by the increasing public pressure to open schools and universities and resume sporting events, when in most places we are not yet ready. Many school districts are making the tragic but right decision to delay in-person learning, buying more time to see how September shakes out. But others are still planning to open, seemingly undeterred by the likelihood that large outbreaks will follow. The New York Times shared a glaring example of this from Cherokee County, Ga., which opened its schools’ doors on August 4 and has already sent more than 900 students and teachers into quarantine. Our projections reveal an even more concerning aspect of this reopening; not only is Cherokee County among the fastest growing outbreaks in the nation, but it is not far from Cobb County, which was among our fastest growing counties in the last two weeks and whose schools open next week. Testing positivity has increased throughout the region, and we will be following that closely as well.

Above are the projections for Cherokee County in Georgia.

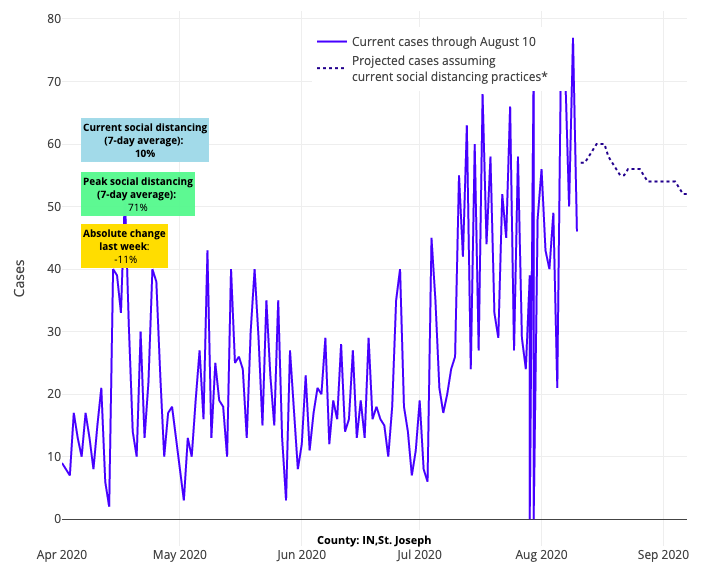

Meanwhile, our college towns are not faring much better. We see sustained or worsening risk for resurgence in South Bend, Ind., Athens Ga., Tuscaloosa Ala., Lexington Ky., and Knoxville Tenn., and the greater majority of college towns in our model have significant circulating cases. As the Pac-12 and Big Ten conferences announced delayed football seasons this week, they surely saw the increased transmission throughout their regions. In these areas, daily case counts have uniformly increased from a few weeks ago, with mean 7-day rolling averages of testing positivity over the last week being 6.2% in counties with Pac-12 schools and 4.7% in counties with Big Ten schools. Most public health experts would agree these are tenuous starting points for university towns that are hoping to prevent rapid spread as their populations quickly grow with students from around their states and the country.

Above are the projections for St. Joseph County in Indiana.

For the optimists out there, we credit Morgantown W.Va. (University of West Virginia) for the exceptional job they have done in eliminating most transmission at the start of the school year, even as Charleston, down the road, is having challenges. And we’d much rather be in Ann Arbor, Mich., which has improved its prospects for the fall, likely through their own efforts, but even more so by being in a state that has managed this epidemic with supreme skill against difficult odds.

Save a few regions that have created environments for possible success by lowering community disease burden substantially (see New York), we find ourselves facing the likelihood that resurging transmission in the fall will originate from our schools and paralyze our nation once again. That’s unless we find the strength to choose a different course—a broad agreement to adopt and maintain distancing, masking and limited gathering size practices that are enforced—that would allow us to create conditions for sustained success until a vaccine hopefully arrives in late winter. The parameters are being set; the only question is what course we will choose.

One final note: If you notice slight alterations to county-level case data in our projections, we sourced our data from the New York Times this week (previously we used usafacts.org), and we also added county-level test positivity data (vs. state data) to better estimate our local area effects. The differences are small, and trends are very similar for most counties. But, for some counties, the addition of county-level data has allowed us to better differentiate counties within the state that appear different from their neighboring counties in increasing or declining test positivity rates.

Gregory Tasian, MD, MSc, MSCE, is an associate professor of urology and epidemiology and a senior scholar in the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. He is also an attending pediatric urologist in the Division of Urology at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.