Why Research Needs Cultural Humility to Support Minority Communities

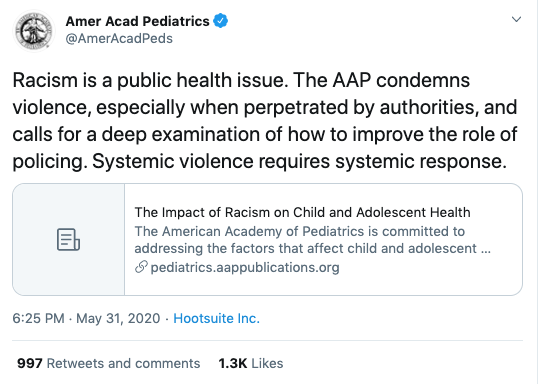

In wake of the recent protests and unrest in cities across the United States, which have drawn increasing attention to ongoing  systemic racism and police brutality against Black individuals, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) shared a powerful statement via Twitter declaring “racism is a public health issue.” They supported this with a link to their 2019 policy statement that connects racism to child and adolescent health outcomes. As a health care community, our knowledge base is constantly expanding regarding the roles that race, and inequities that come from racism, can have on children’s health. These inequities begin at birth, with higher rates of infant mortality for Black babies, and continue well through adulthood, with Black male life expectancy from 1950-2015 consistently being the lowest among Caucasian and Black women and men.

systemic racism and police brutality against Black individuals, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) shared a powerful statement via Twitter declaring “racism is a public health issue.” They supported this with a link to their 2019 policy statement that connects racism to child and adolescent health outcomes. As a health care community, our knowledge base is constantly expanding regarding the roles that race, and inequities that come from racism, can have on children’s health. These inequities begin at birth, with higher rates of infant mortality for Black babies, and continue well through adulthood, with Black male life expectancy from 1950-2015 consistently being the lowest among Caucasian and Black women and men.

In the face of these health inequities, research is an incredibly powerful tool for change. The AAP shares specific ways researchers can be change agents by examining how discrimination impacts adolescent health outcomes. But as we move forward in focusing on marginalized communities, or continue our work we’ve been doing within racial/ethnic minority communities, it’s important to remember the critical importance of cultural humility within research in all of its stages.

As researchers, we must remember that we can’t ever be competent in someone else’s intersectional experience. This idea of cultural competency as something that can be acquired can lend itself to tokenization, or even the exclusion of community representation when we feel like personal competency has been reached. When we conduct research focusing on marginalized communities, we should strive to practice cultural humility instead, which is a commitment to a lifelong process of self-reflection and learning. In centering the needs and voices of marginalized populations at every step, we can honor that individuals within minority communities are the best representatives for themselves, while highlighting the ways racism and other systemic oppressions in health care lend themselves to inequalities.

Why Community Integration Matters in Research

Unfortunately, we haven’t always gotten it right. A lack of transparency about research aims, past and present exploitative studies, and negative framing of results have played a role in alienating minority populations from partaking in beneficial studies and trials. But we can strive to not let history repeat itself by upholding the framework and practices of culturally humble studies.

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is one framework under this umbrella. The CBPR toolkit describes this framework as “an approach to research in which researchers and community members share power, resources, and decision-making at every level of the research process.” By incorporating the community within the entire research process, we can empower communities of participants to provide feedback and maintain a voice throughout the research process.

Though CBPR may be viewed by some as time-intensive or financially infeasible, its successes are clear. Within PolicyLab, faculty member James Guevara’s work has used community-based participatory clinical trials towards testing interventions for Black and Latinx children with developmental delays, with parent and community stakeholder involvement providing critical understanding of the macro-level factors that can impact care for this population. PolicyLab faculty member and Medical Director of Community Asthma Prevention Program (CAPP) Tyra Bryant-Stephens’ founding of the CAPP program laid a successful roadmap toward reducing asthma disparities through utilizing members of the underserved communities to implement educations and prevention strategies in Philadelphia. This community centric approach, guided by a collaborative, is a sustainable model that equips the community to implement asthma interventions. And through the POSSE Project, PolicyLab faculty scholar Marne Castillo’s research has engaged Black and Latinx sexual and gender minority youth at every phase of the research design and execution process to understand how popular opinion leaders can effectively disseminate HIV prevention practices though youth social networks.

When we center knowledge based on lived experience, we can reach effective research results, like reducing health disparities for marginalized groups. Studies have highlighted more effective behavioral and emotional outcomes for treatments that were culturally adapted for minority groups and when studies involved community members.

So how do we ensure community integration when conducting research with minority participants?

Implementing Community-based Participatory Research

We can weave this approach into three parts of the research process: communication, study design and results interpretation.

As we aim to conduct outreach to participant communities, it’s important to prioritize building long-term relationships with community members, faith-based leaders and activists. Long-term relationships create and maintain a space for active community input. Outreach methods that make researchers more visible can be community engagement at town halls and events, rather than recruitment by advertisement. Remaining visible maintains a space for groups to share experiences and needs and feel listened to, as well as for researchers to acknowledge any barriers to trust. Sustaining a presence beyond recruitment can also give researchers insight into any urgent needs of a community that can be addressed with additional research.

Study designs that utilize community knowledge as evidence, defined as experiential evidence by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Evidence Project Overview, show that we value collective experience. We can incorporate community experts’ knowledge on what has and hasn’t worked within literature reviews or policy briefs. Elevating populations’ voices to the same standard as research evidence gives us an opportunity to show validity to lived experiences. This can also be accomplished by ensuring that a member of the vulnerable population is a part of the study’s decision making team along with researchers and investigators.

Finally, interpreting and sharing study results also presents an opportunity for community integration. When data are presented inaccurately, we can potentially imply a community is responsible for negative results. The Economic Policy Institute’s 2019 executive summary noted higher rates of “toxic stress” for Black children, which leads to their increased likelihood for certain health issues, like teen pregnancy. Without the summary highlighting that discriminatory criminal justice practices in Black neighborhoods could be a plausible cause of disproportionate toxic stress among Black children, one could read the findings and assume that Black communities, parents or families inherently shed more stress onto their children.

Without the “why,” researchers may accidentally promote unintended stereotypes for already marginalized groups. Talking with community members and organizations about possible study results, including negative findings, can empower communities to share the “why.” We can tie study conclusions to systems-level oppressions and advocate for structural change in these systems. Sharing results also creates exciting space for community-building opportunities, through which community members and organizations can take the lead on wide-reaching and useful deliverables, like newsletters, webinars or community gatherings.

Better Supporting Marginalized Populations

There may feel like an inherent clash in cultural humility and evidence-based practice. Researchers often emphasize standardization, which can leave out the importance of individualizing interventions for the needs and desires of a given community. We may also face structural barriers like lack of available interpretation for non-English speaking communities or mandated parental consent for participation of LGBTQI+ adolescents who may not have safe relationships with their parents. Creating culturally humble research practice also requires thoughtful design and funding support at the onset of a study. In order to have the necessary resources to engage in these practices, there needs to be more discussion about funding opportunities like those obtained through PCORI to focus on marginalized populations.

However, through revamping our approach to evidence and forming relationships that continue to allow communities to hold us accountable, we can utilize community input as evidence to design and propose creative solutions to combat these and other barriers. As the AAP shared on Twitter, “systemic violence requires systemic response.” Incorporating cultural humility into research is so much more than recruiting a diverse group of individuals to participate in a study. It’s about increasing racial and ethnic minority groups’ connections to and reliance on research as a strategy to highlight injustice, support and influence transformative policies, and position the research community to be advocates that approach research with marginalized patients and families with the fundamental understanding that they, rather than researchers, are the experts in their experiences, needs and solutions.

Pegah Maleki, MSW, is a research assistant at PolicyLab currently enrolled in a Master of Public Health program at the University of Pennsylvania. This blog post was adapted from her fieldwork conducted for her Master in Public Health.