A Vital Tactic for Fighting the Opioid Epidemic: Make Sure Kids Are Safe and Healthy

Drug overdose has become the leading cause of death among people under the age of 50 in the U.S., with opioid addiction resulting in 91 deaths every day. While it’s essential that we invest in treatment and therapies for those suffering from addiction, research shows us that childhood interventions could significantly reduce the likelihood of addiction, thereby helping to stem the tide of this epidemic.

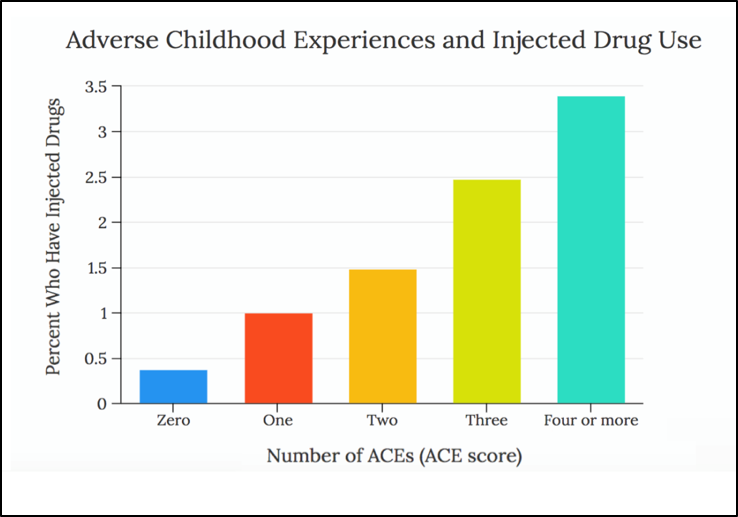

It is well documented that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have an enduring, lifelong impact. ACEs - stressful or traumatic events during childhood that can include a range of experiences such as parental drug use, neglect and abuse, or parental separation - are linked to numerous negative health outcomes including cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and mental health disorders. Similarly, ACEs also have a strong relation to adult addiction. Research shows that people with five or more ACEs are seven to ten times more likely than those with zero to have issues with illicit drugs. In fact, as the number of ACEs a male child experiences increases, so does his risk for injection drug use. (Chart adapted from Felitti, Vincent (2004))

It is well documented that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) have an enduring, lifelong impact. ACEs - stressful or traumatic events during childhood that can include a range of experiences such as parental drug use, neglect and abuse, or parental separation - are linked to numerous negative health outcomes including cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and mental health disorders. Similarly, ACEs also have a strong relation to adult addiction. Research shows that people with five or more ACEs are seven to ten times more likely than those with zero to have issues with illicit drugs. In fact, as the number of ACEs a male child experiences increases, so does his risk for injection drug use. (Chart adapted from Felitti, Vincent (2004))

This relationship suggests that addiction may not strictly be the result of biology or chemistry. If two people inject heroin, what makes one more likely than the other to become an addict? ACE researchers conclude that: “the compulsive user appears to be one who, not having other resolutions available, unconsciously seeks relief by using materials with known psychoactive benefit, accepting the known long-term risk of injecting illicit, impure chemicals.” So, those with unresolved or untreated childhood trauma may be more likely to become habitual opioid users. One contributing factor to the development of addiction may be mental health status. Unsurprisingly, children who experience trauma are also more likely to develop a mental health condition.

The association between trauma and mental health is important to consider - research shows there is a strong link between certain childhood mental health diagnoses and adult substance abuse. For instance, children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are more than twice as likely to have a substance use disorder than those without.

As the country rightly focuses on treating adults currently afflicted with dangerous addictions, we should also be asking ourselves how we can help these at-risk children right now, and protect them from the same devastating fate. Increasing access to mental and behavioral health services for all children is an important first step. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), among children diagnosed with ADHD in Pennsylvania in 2009-2010, only half reported receiving behavioral treatment for the diagnosis. Given the role that trauma and mental health play in substance use disorder, it’s crucial that we provide increased mental health services early to prevent addiction.

PolicyLab is working towards that with its PriCARE project, a group-training program for caregivers provided in a primary care setting and designed to improve child behavior, strengthen parent-child relationships and decrease stress for parents. PriCARE is an example of a promising intervention that aims to prevent child maltreatment and trauma altogether. In concert with expanding access to timely interventions such as PriCARE, we must also work to ensure our social policies and child welfare system - a group of services meant to protect children who have been exposed to unsafe home environments - are effective in creating a safe and loving environment for children.

The opioid epidemic is a complex issue with numerous contributing factors. In addition to our efforts to treat those already suffering, it’s important to be forward thinking and consider the important and frequently overlooked contribution of childhood trauma to the development of substance use disorder.

Rachel Feuerstein-Simon is an administrative associate at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for the Executive Office and the Office of Government Affairs. She is earning her dual Masters in Public Administration and Public Health at the University of Pennsylvania.