No More Watchful Waiting for Developmental Delays

Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released an updated set of developmental milestones as part of the Learn the Signs, Act Early campaign. Before this most recent update, these milestone checklists identified when the average child should reach certain milestones like, for example, using simple gestures such as waving “bye-bye” by 12 months of age. If a child didn’t develop this skill in the recommended time frame, providers could reasonably use a “wait and see” approach, known as watchful waiting, making it easy to say that a child still had time to develop the skill before becoming concerned about delays.

After more than 15 years, the CDC reviewed and adjusted these milestones to make it easier for providers to identify children who would benefit from Early Intervention (EI). Instead of listing milestones at the age when 50% of children are expected to have attained them, the new milestones now list them at the age when 75% of children are expected to have attained them. Now, if a child hasn’t developed that skill by the age listed, clinicians can be certain that most other kids that age are already demonstrating it, which promotes more proactive referrals to EI services.

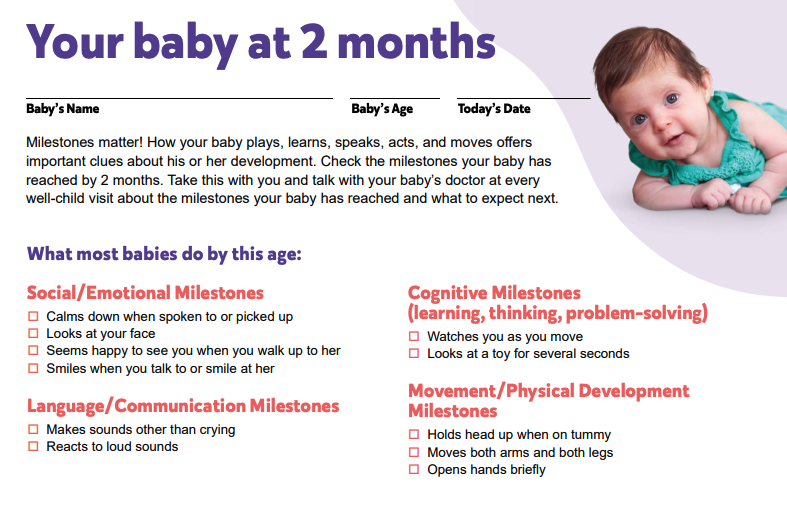

Above is a screenshot from the CDC’s “Learn the Signs, Act Early” materials.

We had a chance to discuss these changes on a recent episode of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Primary Care Perspectives podcast. Here, we dive deeper into why watchful waiting can be harmful to children and the benefits of proactive referrals.

The Importance of Early Identification

The evidence for EI’s effectiveness is strong. When children with delays are identified and begin services early, they are able to make much larger gains than children who delays are identified later. In part, this is because neurocognitive research has shown that there are critical windows of development when learning is most rapid. In addition, a child who receives EI early will have more time to catch up before starting school. In the U.S., EI services are low-cost or free (depending on the state in which a child resides) through the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA) Part C for children up to age 3, with educational systems providing services to kids beginning at age 3 until kindergarten.

To improve early identification and initiation of EI, the AAP has clear guidance to promote developmental surveillance and screening in pediatric primary care, with guidance to refer a child to EI when there is risk of a developmental delay or disorder. The new Learn the Signs, Act Early milestones can help empower families to be more active participants in referral decision-making by arming them with the tools to notice if their child is not meeting milestones and to discuss those concerns with their pediatrician.

Despite the strong evidence and low familial financial burdens for EI, hesitation to refer children who might be eligible persists. For example, Dr. Wallis’ team previously found that even after screening positive for a developmental delay or for autism spectrum disorder, more than 2 in 5 children were not referred to EI on the day of their screening visit, indicating that providers were following a watchful waiting approach. Furthermore, inequities in referral by race and sex were identified, with White boys being referred sooner and Black and Asian children and girls referred later, if at all.

Watchful waiting not only precludes children from accessing EI as early as possible, but it also puts additional burdens on families. During watchful waiting, a family may be told to closely observe a child’s behaviors and make a decision about if or when to call EI directly. Families may have additional challenges navigating EI intake and evaluations without clear guidance from pediatric providers. These burdens and barriers may compound disparities in referral, as the same families who are less likely to receive referrals from a pediatric provider may also face additional barriers to successfully obtaining EI services for their children.

The biggest criticism we’ve heard of the new milestones is that some of the milestones are listed at ages that are too late. For example, saying 50 words is listed as the expectation for 75% of 30-month-old children, when that is already considered by many professionals to represent significantly delayed expressive speech. In light of this criticism, pediatricians should be even more proactive in referring children at these ages.

Moving Forward with Updated Guidance

Families can use the tools offered by the CDC to become active participants in the developmental surveillance process and also use the checklist as inspiration for how to engage their child in developmentally appropriate activities. While awaiting an EI evaluation, the checklists can act as a resource for families who may be unfamiliar with developmental milestones in anticipating the next step in their child’s development.

The new milestones offer clear guidance about ages at which most children should attain a skill, which means that children who have not reached that milestone are likely to be delayed and should be referred for EI services. Pediatricians no longer need to make subjective decisions about which patients they refer and which they use a watchful waiting approach. When it comes to developmental delays, the evidence is clear that we should not wait to intervene. Proactively referring can help all children, but it will also be a step toward improving the equity with which children from racial and ethnic minority groups access and receive EI services.

Katie K. Lockwood, MD, MEd, is an attending physician at CHOP Primary Care, South Philadelphia. She holds a Distinguished Chair in the Department of Pediatrics.