New Legislation Could Harm Children by Concealing Racial Segregation Data from Local Policymakers

While it may sound wonky to many at first, “federal database of geospatial information” is one of those phrases that makes public health researchers, like myself, pay attention.

Geospatial data – electronic data representing things like roads, municipal boundaries or geographic locations – help researchers study where people live and spend time, and how those places impact their health. Data like this has the power to reshape how we think about health problems in our communities and who they affect. Here at PolicyLab, we use geospatial data every day to research children’s health issues like food insecurity or to evaluate home visiting programs. This data can be difficult to collect, but it provides vital context to public health research that no questionnaire or lab test could offer.

Many of the issues we focus on at PolicyLab would be much more difficult to solve without targeted data on our side. Data drives our research and informs our practice and policy solutions to improve child health. In fact, some of the issues we care about are so complex that data provides our only clues into how social systems work.

A great example of this kind of complexity is racial and ethnic segregation and housing accessibility and affordability. There is no single narrative to explain how racial segregation took root in our communities or why it persists; instead, it is the legacy of countless social and economic structures put in place over the last century. We do, however, have plenty of evidence that shows how racial segregation and concentrated poverty have lifelong impacts on the health and economic opportunity of children.

In order to combat the ill effects of racial segregation in housing, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) introduced a rule in 2015 called Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, which builds on the Fair Housing Act of 1968. This rule provides guidance to municipalities receiving federal funds on how to reverse historic patterns of racial segregation and create equitable housing access.

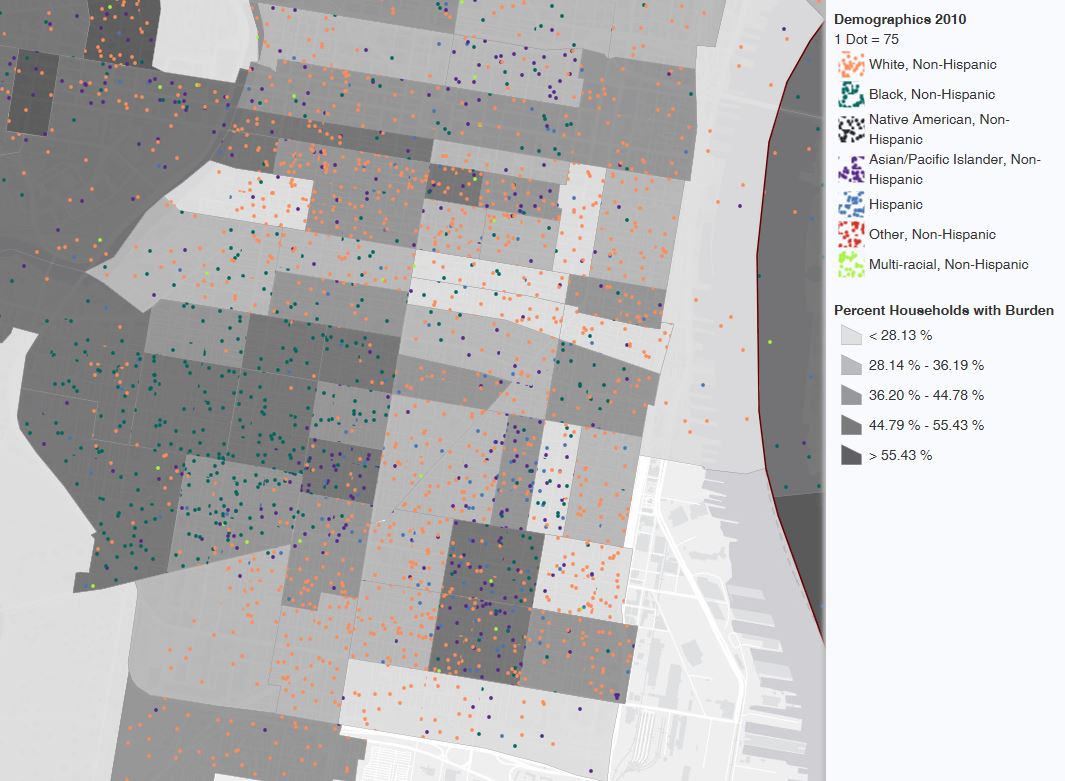

Maybe the most important part of this effort was the creation of a free data mapping tool that allows local governments to better understand what racial segregation looks like in their communities. Through this tool, geospatial data is providing local decision makers with some of their only clues about where racial segregation and disparities in fair housing access exist, and how we can counteract them.

Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing in Philadelphia

[This example map of South Philadelphia shows areas with a higher burden of housing problems that have disproportionately affected minority populations.]

Unfortunately, the open dissemination of this information is now at risk. In January of this year, bills were introduced in the House and Senate to reverse the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule, citing the importance of local autonomy in zoning decisions. Most importantly, though, these bills include the following language:

“Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no Federal funds may be used to design, build, maintain, utilize, or provide access to a Federal database of geospatial information on community racial disparities or disparities in access to affordable housing.”

Regardless of the intent behind this legislation, it would effectively eliminate an important tool for understanding a deeply-engrained, yet elusive problem that exists to the detriment of children’s health. The end result would mean that local policymakers would have less information to inform their decisions about addressing housing needs and reaching populations with limited access to affordable housing. We especially care about this at PolicyLab because children without access to quality housing can disporoprtionately experience a host of poor health outcomes, including lead poisoning or exposure to environmental asthma triggers.

As researchers, we are often unable to rigorously document the chronic problems that we know are present in our community. In this case, however, the information needed to begin addressing the problem already exists. All Americans benefit when policymakers embrace objective information whenever it is available. Racial segregation and its impacts on health will persist, especially if we lose the tools to examine it, which begs the question: what do we have to gain by knowing less?