Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and the Opioid Crisis: Paying Attention to Social Context

As you likely continue to read in your local news or experience in your community, the United States is in the midst of a deadly drug overdose and addiction crisis. In fact, overdoses claimed the lives of 70,000 individuals in 2017—more than two-thirds of those overdoses were linked to opioids.

While drug overdoses disproportionately affect young adults, there are also important downstream effects on children and families. One such effect is neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), a withdrawal condition that is the result of prenatal exposure to opioids.

The Stigmatization and Criminalization of NAS

NAS has received increasing public attention as the number of children diagnosed with NAS more than tripled from 2000 to 2012. NAS can result from maternal use of prescription opioids, illicit opioids (heroin and fentanyl) and as an expected side effect of the medications used to treat opioid use disorder (methadone and buprenorphine). Children born with NAS often require intensive care and may be at risk of additional complications. However, with appropriate medical attention, medical providers can typically manage NAS without long-term side effects to child health.

Even though it is a treatable condition, the rise in NAS has encouraged the perpetuation of stigma against pregnant women who use opioids and efforts to criminalize maternal opioid use. Several states have proposed draconian new laws that would create criminal penalties for exposing fetuses to drugs. Public discourse has focused on the “bad behavior” of the mothers, and news reports have described babies with NAS as “addicted to opioids” (in fact, while the babies are physically dependent on opioids, they are not addicted since addiction is a behavioral disorder). Absent from much of the news coverage is a wider context on the social and economic conditions that often give rise to NAS. Poverty, unemployment and poor access to medical care are much greater risks to the long-term health of newborns than NAS on its own.

The Impact of Community Social Stress on Opioid Use and NAS

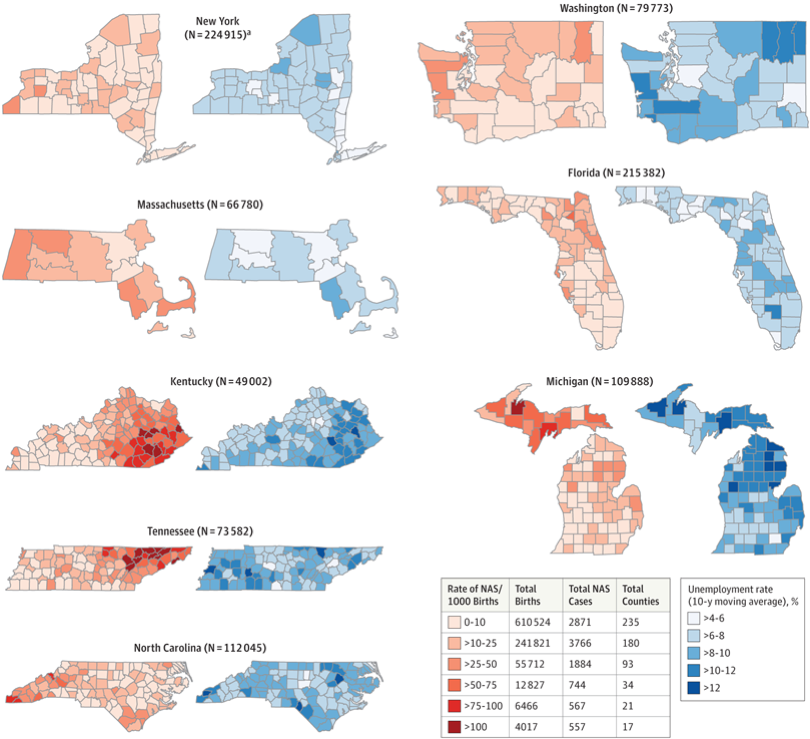

To bring this wider context back into the conversation about NAS, a research team led by Dr. Stephen Patrick at Vanderbilt University recently published a study in JAMA that examined the association between trends in county-level rates of NAS and factors like the unemployment rate and availability of mental health services and primary care across 580 counties from 2009 to 2015. The authors found that areas in which residents had fewer mental health services available to them had higher NAS rates. One notable finding was that the researchers reported the 10-year unemployment rate of a county was associated with strikingly higher rates of NAS—roughly a threefold difference in incidence between the areas with the highest unemployment rate and the areas with the lowest unemployment rate. You can see the close patterning between NAS incidence and unemployment rates in the figure below.

What is going on here? The authors proposed that their study findings are consistent with the idea that communities with higher levels of social stress are also more susceptible to substance use disorders, including opioid use in pregnancy. There is no doubt that poverty and substance use often travel together, and can be a particularly toxic stressor during pregnancy.

Existing Interventions that Could Help Families Impacted by Opioids

For clinicians and public health advocates, the JAMA study is another reminder that if we only focus on substance use in pregnancy we are unlikely to address the underlying social conditions that cause pregnant women to engage in a range of unhealthy behaviors including tobacco and alcohol use and unhealthy diets. Additionally, it is important to continue to communicate that NAS on its own is not a scar for life—it is a manageable condition.

There are many effective ways to help mothers who use opioids with treatment and recovery. I would argue that in addition to improving access to treatment and recovery services, what is important now is that researchers evaluate how extending the broader set of public health and clinical tools that have already been shown to reduce pregnancy complications and child welfare involvement—including nurse home visitors, food and housing assistance and incentives to use prenatal care—could assist families impacted by the opioid crisis in addressing their overall well-being and health trajectory. While these targeted interventions will never completely overcome the stress of living in poverty, they are effective tools for improving child health from the time they are born and may be particularly helpful for families and communities at high-risk for opioid use disorders.

Brendan Saloner, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.