Adverse Childhood Experiences: Addressing Trauma Nationally and in Philadelphia

Children experience a parent’s prolonged absence as a loss; they are frightened by witnessing violence and other direct threats to their physical safety; poverty restricts their access to the basics (healthy food, safe housing, medical care, cognitive stimulation) that support their development. Fundamentally, these and other adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) threaten a child’s sense of security. They may lead to toxic stress, which can hinder a child’s development and leave them with behavioral and health problems that ripple throughout life.

Especially when they have had multiple exposures to these kinds of trauma, children’s bodies respond by releasing stress-related chemicals. Those responses, in turn, affect how the brain works, and the body’s capacity to ward off disease. The longer-term results can take many forms: problems with attention, decision-making, and behavior; depression; chronic illness; alcohol and substance abuse; reduced earnings; and shortened life expectancy.

At Child Trends, we recently released a report on ACEs that showed nearly half (45 percent) of all children in the United States have experienced at least one ACE, and one in ten has experienced three or more ACEs, placing them at especially high risk. These are compelling findings, and demonstrate the magnitude of the role ACEs play in the lives of our nation’s children.

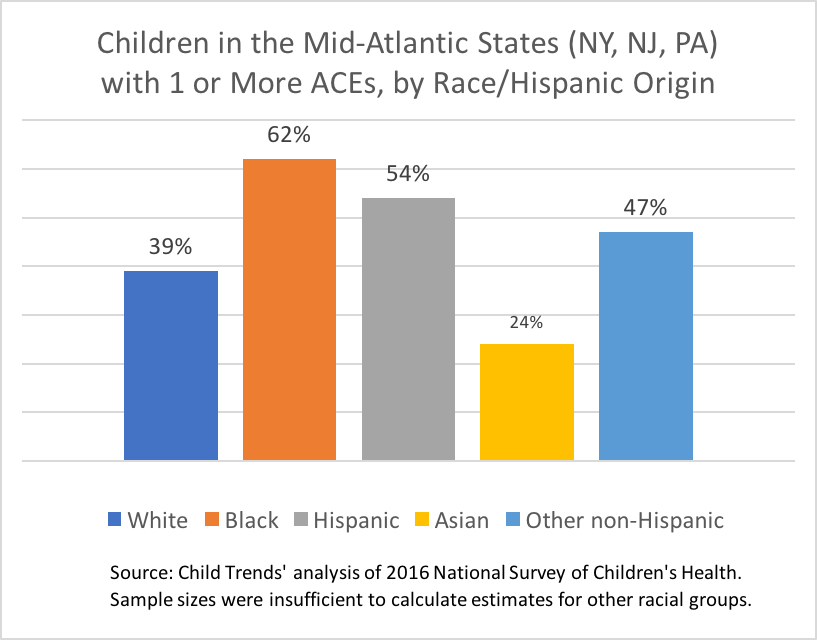

We used the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health to examine the occurrence of eight ACEs (as reported by a responsible parent or guardian), for the nation, and for each of the states. Because the risk to health and well-being is especially great when a child has had multiple ACEs, we also show the data on the percentage of children who have had two or more of these experiences. We also found that children of color are most affected by ACEs, which reflects the intersection of multiple forms of discrimination. For example, 61 percent of black non-Hispanic children, and 51 percent of Hispanic children, have had at least one ACE, compared with 40 percent of white non-Hispanic children and only 23 percent of Asian non-Hispanic children.

Unfortunately, as a scan of recent headlines makes clear, the list of ACEs, as both cause and effect, is long: gun violence, opioid abuse, sexual harassment and abuse, separation of immigrant families, military conflict, homelessness, and grinding poverty. All of these have multiple causes and consequences, of course, but the role trauma plays here is difficult to ignore.

While we cannot eliminate trauma, we can reduce its prevalence, especially our children’s exposure to it. We can also interrupt the disturbing transmission of trauma from one generation to the next.

Trauma requires us to focus on both survivors and perpetrators—uncomfortable as that may be—because those who perpetrate trauma are often the survivors to whom we earlier failed to give appropriate help and support.

Philadelphia’s Innovations in Assessing ACEs

Philadelphia has been at the forefront of communities taking a hard look at ACEs, widening the lens we use to think about these concepts, and grounding them in the realities of a particular city.

In 2012 and 2013, Philadelphia residents participated in a survey designed by the Philadelphia ACE Task Force. This survey broke new ground by including, in addition to the items used in the original ACEs study, several items pertaining to adverse experiences affecting children at a community level: racism, witnessing violence, unsafe neighborhoods, bullying, and experience in foster care.

These experiences (and, of course, others) more closely reflect the lives of residents of a racially and socio-economically diverse city. In fact, survey results showed that these additional items not only picked up unique patterns of risk, but that the more limited set of ACEs substantially underestimated the prevalence of potentially traumatic exposures.

This work helped change the conversation around ACEs. It expanded the focus on individuals and families, to include community and societal sources of trauma. It also reframed discussions about resilience—identifying this as a priority to promote at a community level, as well as within families and individuals.

We have the tools to protect children from ACEs, to heal the wounds that ACEs can inflict, and to increase resilience. By and large, they are the tools of healthy relationships—tools which, where they do not exist, can be taught and learned through patient practice. However, their success depends on policies that embody a caring community: adequate parental leave and other supports for new parents, comprehensive health care, and a rejection of violence and the easy availability of deadly weapons. All of us who work on behalf of children can help inform policymakers of these opportunities to reduce the threats posed by ACEs.

David Murphey, PhD, is a research fellow and director of the Child Trends DataBank at Child Trends.