Are Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives the "Holy Grail" for Preventing Teen Pregnancy?

The vast majority (80-90 percent) of teen pregnancies in the United States are unintended. While four out of five sexually active teens use contraception, they often rely on methods that have high failure rates due to incorrect use, such as partner withdrawal, condoms or birth control pills. For every 100 women who rely on condoms as their primary method of contraception in one year, 20 pregnancies will result, and for every 100 women who rely on the pill, 10 pregnancies will result.

In contrast, for every 100 women who rely on long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), only one pregnancy will result.

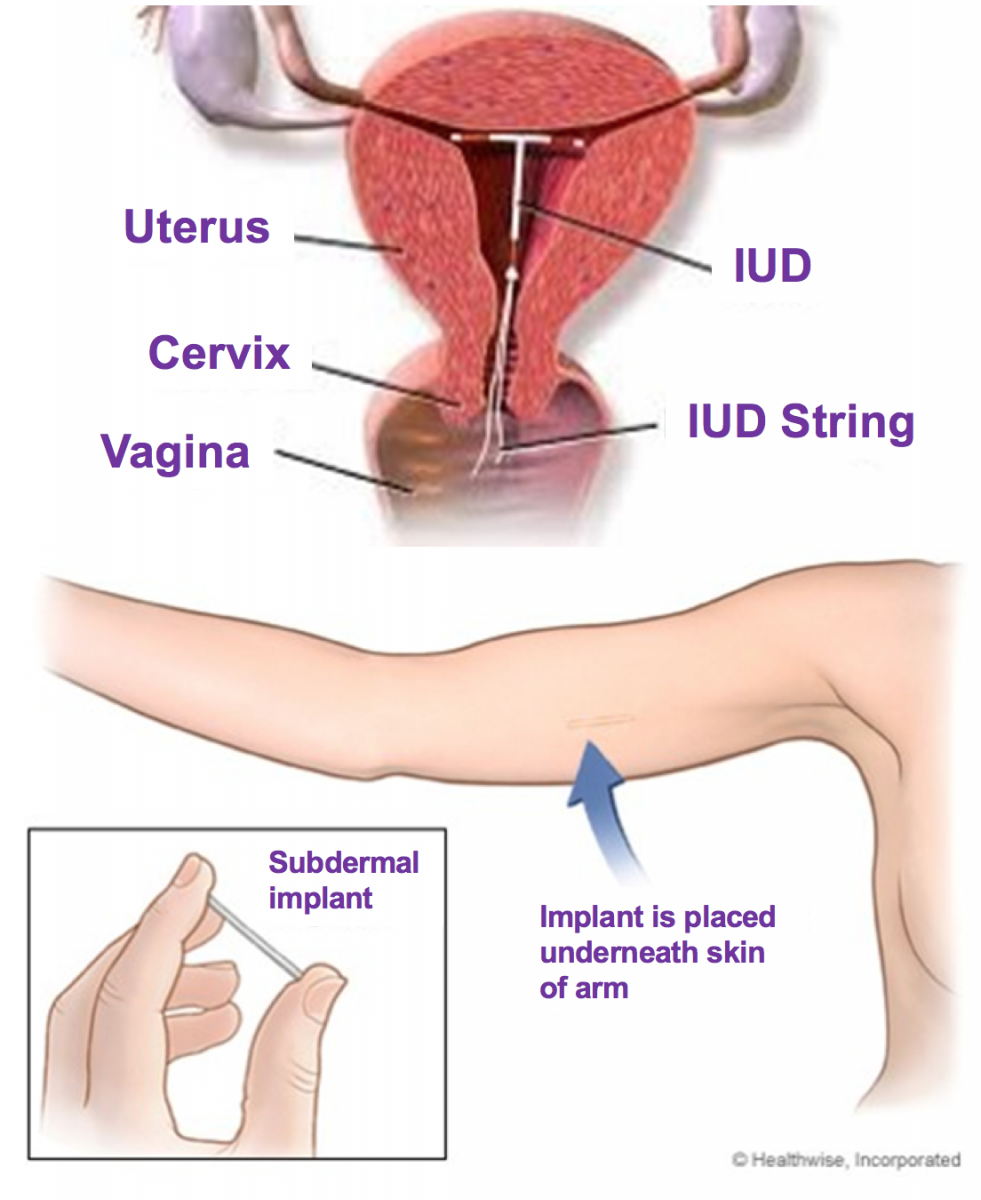

LARCs are medical devices that are placed either under the skin of the arm or inside a woman’s uterus, as shown in Figure 1. They are safe, highly-effective birth control methods that women can use for 3-12 years, depending on the method. Once placed, LARCs have the benefit of being “forgettable,” meaning the device will work until it is removed.

Figure 1

Because they are very effective, easily reversible and serious complications are rare, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization, American Academy of Pediatrics and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine are among the many national organizations that recommend LARCs as a first line contraceptive for teens.

Despite LARCs being a recommended, safe and effective contraceptive method, less than five percent of teens in the U.S. use them. While this number is slowly rising, it remains substantially lower than in other Western developed countries.

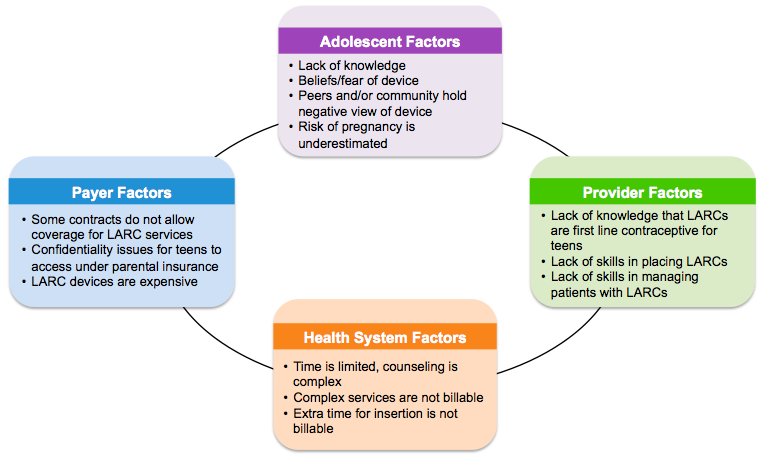

There are a number of barriers to the use of LARCs among U.S. teenagers, one of which is cost. However, while they cost more up front, they are much cheaper than many other contraceptive options after 12 to 18 months of use.

As you can see in Figure 2, there are also many patient, provider, health system and insurance barriers.

Figure 2

When cost and access barriers are removed, LARCs can be a crucial tool for preventing unintended pregnancy. An increasing number of population–based studies have shown the promise of LARCs for reducing unintended teen pregnancies. An intervention in Colorado provided access to low-cost or no-cost contraceptives, including LARCs, and successfully cut the teen birth rate nearly in half between 2009 and 2014.

So how can we encourage more teens to consider LARCs as a contraceptive option?

- Education for Teens and Families: We need to expand access to counseling services for teens and their families on the safety and effectiveness of LARCs as a contraceptive option and about their other uses. Not only do LARCs prevent pregnancy, but they can also help teens manage menstrual problems, can be used as emergency contraception and can be a particularly useful option for teens with cognitive or physical disabilities, those on teratogenic medications and for those with chronic medical problems whose health would be compromised by an unintended pregnancy.

- Education for Providers: We need to teach providers about the benefits of LARC methods, about how to best counsel teens and their families, how to properly place and remove LARC devices and how to manage patients who are using LARCs.

- Address Systems-Level Issues: We need to streamline the LARC supply and billing process and increase reimbursement to compensate providers for the additional time required for counseling teens and their families and for placing the devices.

- Address Confidentiality Issues: We need to address the fact that while teens may be legally entitled to confidentiality regarding their reproductive health, insurance companies may reveal information about these services to the parents as part of routine reporting.

By addressing these various issues, we can increase teen access to LARCs and substantially lower the rates of unintended pregnancies among teens.

An important question remains: Are LARCs the “holy grail” for preventing teen pregnancy? Although LARCs may substantially decrease teen pregnancy and abortion rates, we must remember that there are multiple factors contributing to an adolescent’s risk of having an unintended pregnancy. Poverty – particularly multigenerational poverty – along with low educational status, lack of sex education, substance use and coercion by partners, among other things, all contribute to a teen’s risk of experiencing an unintended pregnancy.

Therefore, reducing unintended teen pregnancies will continue to require both making LARCs more easily available as a contraceptive option along with increasing access to quality education and social services for all of our nation’s adolescents.