Hello Philly: a guest blog post from Philadelphia’s health commissioner

Thomas Farley, MD, MPH, is the health commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. Dr. Farley, a pediatrician by training, came to Philadelphia in February 2016 after serving as the health commissioner for New York City from 2009-2014. He recently spoke at a PolicyLab staff retreat about the health crisis this city is facing, particularly among youth, and his broad plans for how to tackle some of the health challenges facing Philadelphia’s children. We asked him to expand upon those thoughts for the PolicyLab blog.

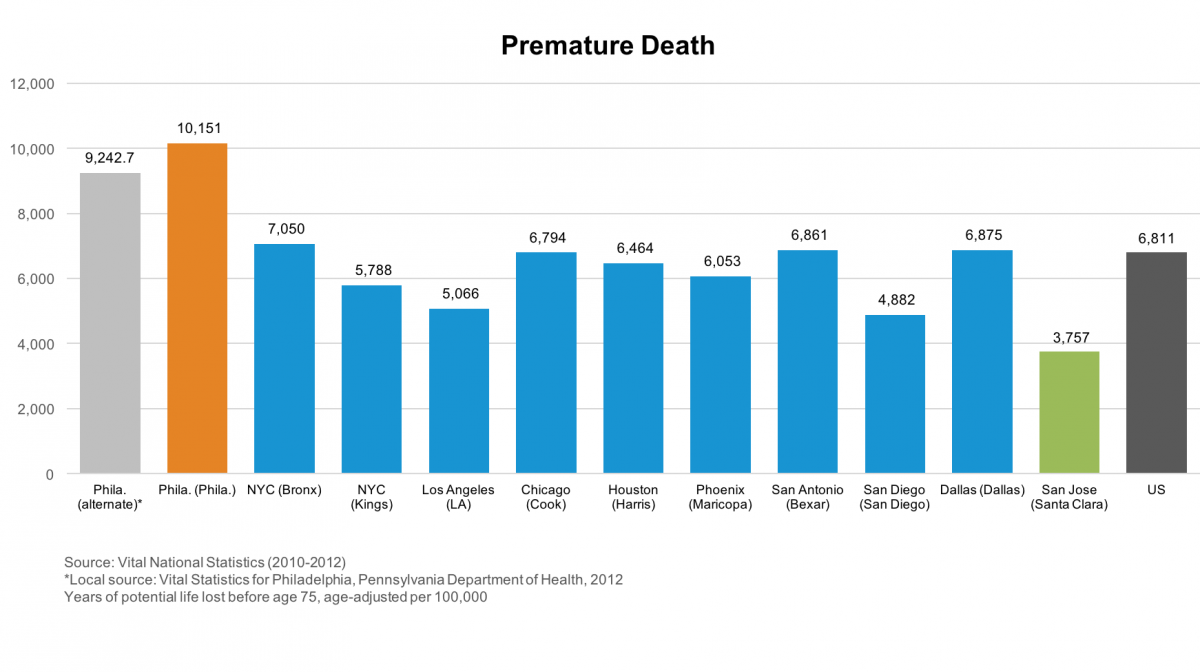

Although I’ve been here for seven months, I still feel new to Philadelphia. It’s a wonderful city – easy to get around, with plenty to see and do – and people here have been very welcoming. At the same time, Philadelphia has statistics that put it among the least healthy of the nation’s biggest cities. Those health statistics tend to track poverty, and are no doubt worse in Philadelphia because of the city’s high poverty rate and the legacy of economic and social problems (like a disappearing manufacturing base) that we all inherited.

My job, and the job of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, is to do whatever we can to change those disturbing health statistics. Here’s how I think through that problem: the biggest killers in Philadelphia, as in the rest of the U.S., are chronic diseases - like heart disease, cancer and diabetes – and injuries, like those caused by guns. We prevent these problems by attacking the risks that cause them.

The causes of poor health fall in two broad categories: 1) behavioral and environmental determinants, and 2) social determinants. The key behavioral and environmental determinants are mostly familiar: smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, alcohol and drug use and air pollution. The key social determinants, which overlap and exacerbate each other, include poverty, income inequality, inadequate education, joblessness and racial segregation. Social determinants do their damage over a life span. That is, children living in impoverished, segregated neighborhoods are more likely to suffer a combination of adverse experiences, like having a parent who is suffering from mental illness or incarcerated; these adverse experiences increase the risk that these children will suffer from mental or physical illness when they become adults, reinforcing the cycle. We can and should take on these social determinants at the same time we address behavioral and environmental determinants.

And there are many things we can do to take these on. For example, Mayor Kenney’s sugary drink tax simultaneously tackled a key behavioral determinant (unhealthy diet) and a social determinant (inadequate education) by nudging people to switch from sugary drinks to water and using the tax revenue to expand pre-K for poor children. Another example: the Board of Health just passed regulations that will gradually reduce the number of retail stores selling cigarettes in poor neighborhoods, particularly around schools. That will ultimately cut down the number of teens who take up smoking, the number of adults who smoke and the number of young children with asthma attacks because of second-hand smoke at home.

Both of those examples involve changes in policies. While we can and should operate programs to alleviate behavioral and social determinants, I’m a big believer in policy change as a way to promote health. The reason is basic economics: well-designed and -implemented policies can affect everyone at little or no cost, while programs almost never have enough funds to reach everyone who can benefit from them. At the health department, we’ll be looking for policy levers that can alleviate Philadelphia’s most important public health risks. And as we do we’ll need help from everyone, including the experts at PolicyLab, who wants to pitch in.

Thomas Farley, MD, MPH

Thomas Farley, MD, MPH