Community Engagement is Vital to Solving Local Health Problems

Editor's note: This post is part of our series in recognition of PolicyLab's 10th anniversary and our ongoing efforts to chart new frontiers in children's health research and policy. Read the first post here, and check back for more content throughout the year!

As one of PolicyLab’s founding members, I have had the privilege of conducting research in the city of Philadelphia for over 17 years. Philadelphia is recognized as one of the poorest of the 11 largest cities in the U.S. As a consequence, Philadelphia’s children are in relatively poor overall health compared to children in other large cities: ranked highest in obesity, smoke exposure, infant and child mortality, low birth weight births and violent crime, and lowest in on-time high school graduation. Yet these statistics belie a vibrant and diverse community, committed to improving the lives of young children. I know this to be true, since I’ve worked with many community organizations and their leadership on projects to improve the lives of Philadelphia youth.

As a result, I have come to value community-engaged (CE) research in my approach to addressing important child health problems. But what is CE research? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has defined community engagement as “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people.” Therefore, CE research is a collaborative process that involves academic researchers and community members working together to solve vexing health problems that neither is adequately positioned on their own to solve.

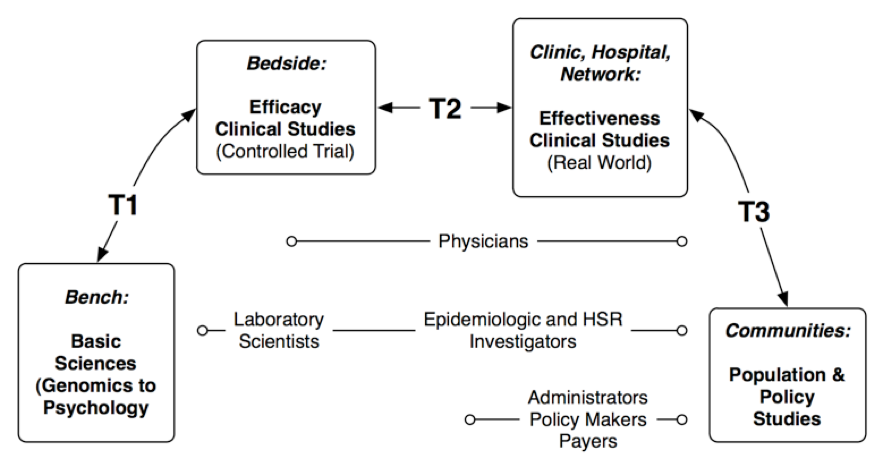

Through CE research, community members bring insight and local knowledge of community health problems to the table, while academic researchers bring an understanding of research design and study conduct. Community members help researchers prioritize research questions, identify appropriate research designs and interventions and interpret and disseminate findings to empower the community. This results in research findings that establish generalizable knowledge while being relevant to the context in which they are placed and, therefore, positioned to improve community health. In the lexicon of research phases, it is considered to be a T3 translational study.

It is exciting to see the growth in CE research since the founding of PolicyLab. Many PolicyLab investigators are turning to CE research designs to address questions of public health importance, including smoking cessation, obesity, school violence, racism, maternal depression and immigrant health to name a few. Understanding the importance of collaborative partnerships to develop sustainable solutions, my colleagues are developing projects that involve the local health department, advocacy organizations, schools and service providers.

Take as an example a project that I’m partnering on with Drs. Marsha Gerdes and Katherine Yun. We are working with members of the city of Philadelphia’s Division of Intellectual disAbility Services, KenCrest and Public Health Management Corporation to study the effects of patient navigation for children with developmental delays who have been referred to Early Intervention. Members of these community organizations have the intimate knowledge of how Philadelphia’s Infant Toddler Early Intervention Program works and are positioned to disseminate our research findings locally. It has been an empowering and fruitful partnership that is only increasing our ability to develop evidence-based sustainable solutions for these youth.

As we mark PolicyLab’s 10th anniversary and think about charting new frontiers in children’s health policy, I expect that PolicyLab investigators will continue to rely on CE research to address difficult problems and to help improve the lives of Philadelphia’s children. I look forward to partnering with them and with our community partners on this exciting research.