A Running Start in Health

Harmful exposures in early childhood, such as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), can hurt children’s physical and mental health, with consequences that last a lifetime. Preventing these exposures among Philadelphia’s young children today can greatly improve the health of children and adults tomorrow. But the sheer number of harmful influences make it difficult to decide where to invest time and resources.

In early July, Mayor Jim Kenney unveiled a new agenda for children’s health, called A Running Start – Health, which targets the most important problems of early childhood. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health and other city agencies developed this plan – a companion to the education plan A Running Start – Early Learning – to focus city-wide efforts on children’s health, and the city is now inviting organizations of all types that care about young children to sign on.

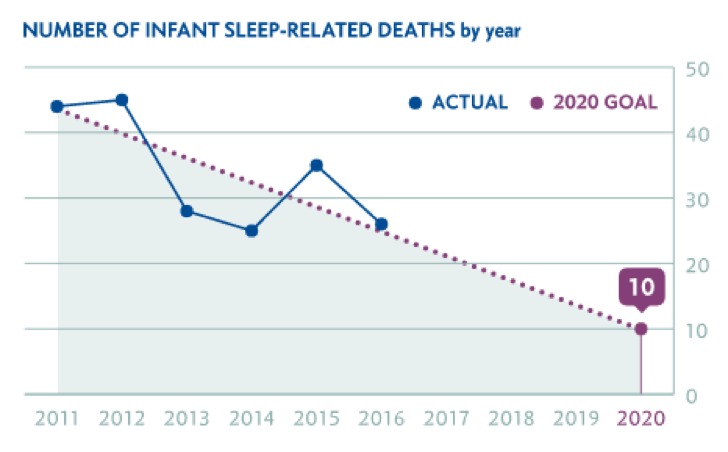

The plan identifies seven key adverse outcomes, chosen either because they are major preventable causes of morbidity and mortality in young children or they are early (and measurable) markers for major causes of morbidity and mortality in adults. Those outcomes are: sleep-related deaths, delayed early development, lack of school readiness, injuries, asthma exacerbations, lead exposure and obesity. The plan identifies targets for those adverse outcomes by 2020, for example, reducing sleep-related deaths from 26 in 2016 to 10 in 2020.

Reducing sleep-related deaths by about 60 percent in four years is ambitious, as are the other goals. To reach them, A Running Start – Health identifies exposures that put children at risk and then defines interventions that will reduce these risks. For example, unsafe sleep practices and lack of breastfeeding are risks for sleep-related deaths, educating about safe-sleep practices, and supporting breastfeeding during home visits are interventions that will reduce them. There is not a one-to-one correspondence between interventions and risks, or between risks and adverse outcomes. Fortunately, many interventions can address more than one risk or help reduce more than one outcome.

In total, A Running Start - Health lists ten key interventions. Then in its “Action Plan”, A Running Start – Health lists very specific steps that nearly any organization can take to help put these interventions in place. For example, to help promote breastfeeding, a social service organization’s staff can talk about the value of breastfeeding whenever they meet with new mothers. Health insurers can make sure that each mother has a home visit by a nurse to help support breastfeeding in their baby’s first week of life. Businesses can provide lactation rooms and establish breastfeeding-friendly practices for employees. And hospitals can adopt the practices that designate them “Baby-Friendly”.

Those of us at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health are excited to have partners that have already committed to help support A Running Start - Health. For example, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), the primary care provider to more than 250,000 children in the region, and its PolicyLab have pledged to encourage moms to breastfeed, connect parents to home visiting services, address hazards in the home and provide books to support early development. Other organizations, including community health clinics, maternal-infant health organizations and social service agencies, have also made commitments, and every organization can get involved by going to runningstarthealth.phila.gov and clicking on “How to Help”. If the plan gathers momentum, every child in Philadelphia will indeed get a running start in life.

*Chart source: City of Philadelphia. Department of Public Health. Number of sleep-related infant deaths as classified by Medical Examiner. CY2011-2016. Medical Examiner’s Office. Coroner Medical Examiner (CME). Database. (Accessed May 4, 2017).

Thomas Farley, MD, MPH, is the health commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. Natalie Kotkin is the special advisor to the commissioner.