COVID-19 Outlook: A Second Wave to Blanket the Nation

As we venture deeper into October, the calculus continues to evolve for schools. In recent weeks, the focus for most schools was to establish strategies that would allow classrooms to reopen for in-person instruction. Now, as the country faces a growing fall wave, the goal is to remain open by fortifying safety protocols that minimize the likelihood of outbreaks originating within school walls, either between students or from students to teachers.

Last week, we highlighted that in the presence of strong safety plans and community vigilance to mitigation practices such as masking and distancing many schools have done well, even as case incidence—and hospitalizations—were rising in the northern U.S. While our local health departments in the Philadelphia region are seeing students and teachers become infected each week, they’ve reported that those cases have been principally community-acquired, suggesting that risk for exposure to COVID-19 is higher when teachers, staff, and students are out of school and not benefiting from the safety protocols of the school day.

Now is not the time to reduce mitigation efforts in schools, but rather to fully commit to these strategies that have allowed us to safely reopen. We do not yet know the upper bound of community incidence that can overwhelm the multi-layered safety plans schools have developed, but should linked transmission occur within schools or case counts begin to accelerate quickly within their communities, our public health leaders will be key partners to school leaders in making difficult decisions about when to revert to virtual learning.

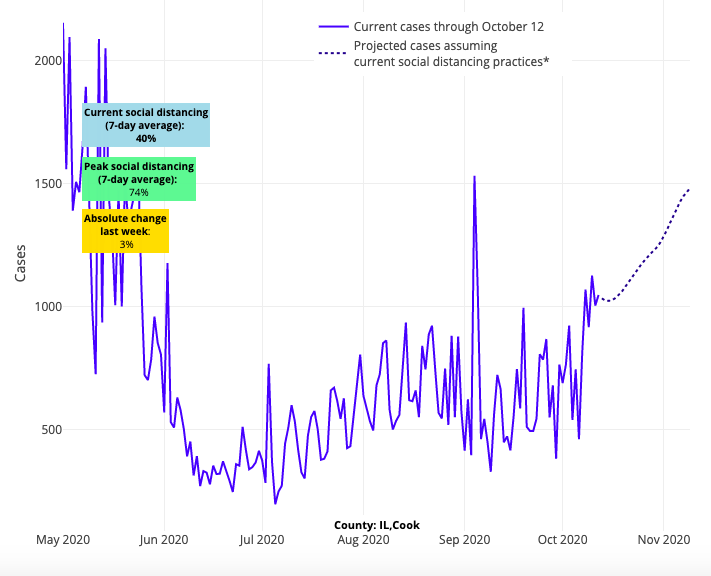

This week, as we survey the country in our PolicyLab forecasts, we see the potential pressure of increasing caseloads rising in many areas. This next wave is now blanketing a larger portion of the nation. For those looking for signs that the Midwest resurgence will slow down, that has not happened—quite the contrary. Case counts are expected to increase over the next four weeks in all of the midwestern states as testing positivity rates continue to climb, married to quickly increasing hospitalizations. All eyes need to be on the Chicago area as it is moving toward exponential growth again. Omaha is surging, and Indiana and Iowa are not far behind. Although not as quickly as other states, Ohio and most counties in Michigan have also worsened.

Above are the projections for Cook County (Chicago) in Illinois.

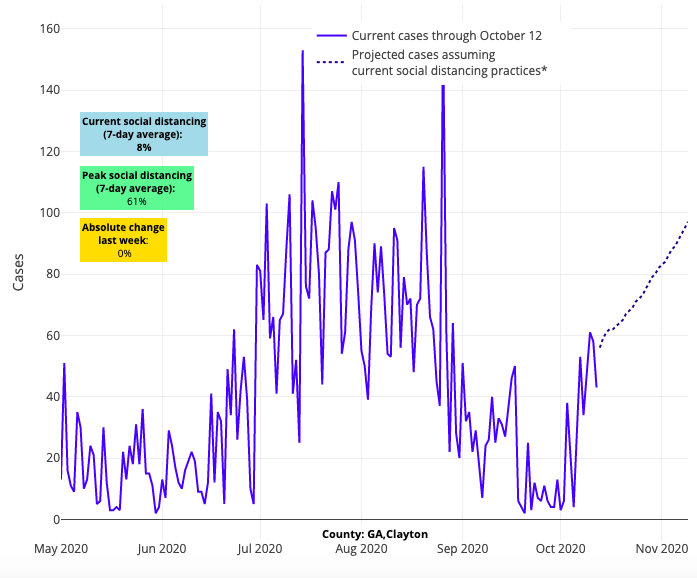

What’s more, we are also now seeing evidence that this new wave is pushing south. While lapsing local restrictions and waning public vigilance is contributing to the quick spread of community transmission across the country, we should not underestimate the geographic acceleration of the pandemic that is being driven by cooling temperatures. The Mid-Atlantic is now past its nadir as our forecasts for Maryland and Virginia have worsened. We see clear resurgence risk in Tennessee, Georgia (specifically the Atlanta area), and areas throughout the Carolinas, which are all experiencing higher case incidence and growing test positivity rates.

Above are the projections for Clayton County in Georgia.

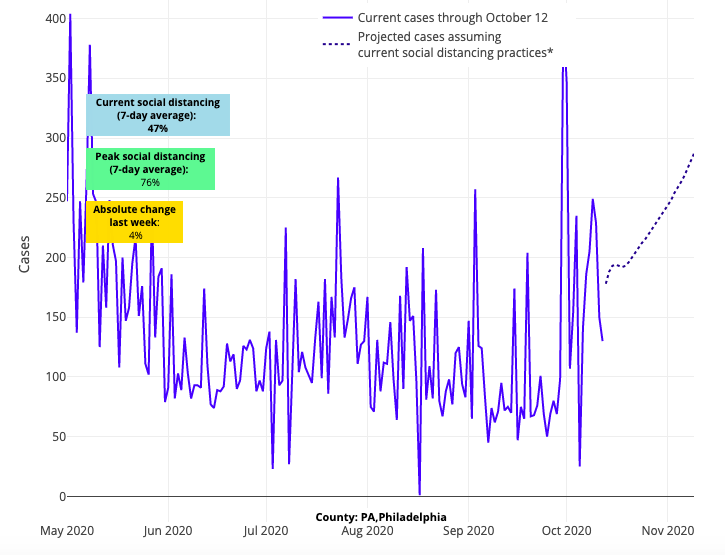

A silver lining is perhaps found in the response of states across the Pacific Northwest and Northeast to warning signs of resurgence risk that we reported last week. While transmission rates are also growing in these areas, it is not at the same pace as the middle of the country. Projected case growth decelerated slightly in our forecasts this week for Washington and Oregon, and testing positivity rates are growing at a slower pace in Massachusetts and New York compared to neighbors to the south. The Philadelphia region shows similar trends with lower but increasing slopes, although we would caution that our hometown is getting heavy pressure from more quickly deteriorating neighboring counties to the west, specifically Lebanon, Berks, Lancaster and York.

Above are the projections for Philadelphia County in Pennsylvania.

We have to assume these areas that have tempered the rise in cases are responding appropriately to the growing resurgence risk surrounding them, whether through increased attention to individual protections and/or the implementation of contact tracing and quarantine by public health authorities. Whatever the reason, the resistance in these areas provides some hope they can weather the storm… but it is still early fall, and the road only gets harder from here.

As you can see, our schools’ efforts to protect their reopenings has gotten harder in most areas of the country. But, even as community incidence worsens, there remains an opportunity for school safety plans to become even stronger. Here are the most salient questions that are now arising:

1) Are youth sports contributing to this wave?

As youth sports resume, often in conflict with public health departments’ concerns, we are finding out more every day about the nature of risks to youth sports leagues, specifically within the context of competition. Some of that information is coming directly from contact tracing when young athletes acquire COVID-19, which, many would be surprised to learn, shows little transmission happening during gameplay even in sports where athletes are unmasked. These data are augmented by the contact tracing of professional sports leagues that similarly suggest limited transmission occurs during gameplay. For example, we learned most recently that an outbreak within the Tennessee Titans professional football team did not result in transmission to any Minnesota Vikings players, against whom they played the week the outbreak began.

Although transmission is not occurring during gameplay, caution is still needed as these are limited sample sizes. Further, we are detecting some spread among young athletes that cannot simply be explained by community infection rates. The reason, we believe, has more to do with the actions of the athletes and their teams off the field than on it. From pre-game meals, to post-game parties, to unmasked journeys home on the bus, to the poorly ventilated locker rooms, we are honing in on the primary drivers of transmission.

We need to focus more on the team’s actions off the field than on it if we wish to protect our athletes and minimize the likelihood of outbreaks spreading first through teams and then to family and community members that team members come into contact with.

2) What if our school cannot achieve one of the safety steps as they reopen? Will we fail?

We began to address this question a couple of weeks ago when we discussed the strength of a multi-layered school safety plan, in which strict adherence to each step is likely never realistic. There will be kids who break the six foot threshold; some will inevitably pull of their mask at the wrong moment; a pre-symptomatic or early symptomatic child will eventually come to school. But, if a school truly commits to multiple layered interventions, individual breaches of the strategies would need to occur at the same time to lead to an outbreak within school walls.

Therefore, at times when community incidence is high enough that we might expect several students and a couple of teachers to test positive every week, we need to resist the urge to quickly shutter schools and rely on our contact tracing to: 1) establish if the transmission occurred within the school; and 2) if it did, provide guidance to the school leaders on how to halt the continued spread of transmission and strengthen safety plans to minimize the likelihood of a similar event happening in the future.

Layering strategies are also recommended for youth sports, choirs, drama clubs, and even in smaller-sized classrooms in which achieving six foot distancing can be challenging.

Ultimately, our accommodation to COVID-19 is going to require strategic thinking, acceptance of effective protocols and flexibility in our safety plans. There may be disagreements of where those opportunities exist (e.g., modified quarantines), but achieving compromise through multi-layered plans may be our best bet to balance the tradeoffs of managing the pandemic and restoring some normalcy to our lives. And if we emerge on the other side of winter somewhat more balanced than we were at the end of the last one, we will be all the better for it.

Gregory Tasian, MD, MSc, MSCE, is an associate professor of urology and epidemiology and a senior scholar in the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. He is also an attending pediatric urologist in the Division of Urology at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.