Reducing the Use of Antipsychotic Medications Among Children in Medicaid: A Role for System Design?

Guest blogger: Brendan K. Saloner, PhD; Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health

Use of psychotropic medications has risen steadily in the last two decades. In 2005, one in seventeen children in the Medicaid program was prescribed medication for a mental health condition, and the rate for foster care youth was one in four children. These children –often coming from distressed home environments – represent a major challenge for their providers, teachers, and caretakers. While most skilled clinicians agree that medications can play an important role in managing the behavior of children with severe emotional and behavioral problems, there is also recognition that these drugs have the potential to cause harm when prescribed indiscriminately. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are of particular concern because these powerful medications are very expensive and carry side effects such as weight gain.

Interventions to reduce the use of SGAs in Medicaid often focus on the behavior of prescribing physicians. For example, states have placed SGAs on lists of medications requiring prior authorization or have created patient registries to track prescriptions of these medications. Less discussed is the potential role of systemic interventions that focus on the coordination and integration of broad categories of mental health services. If children receive mental health services that are overseen by a third-party managed behavioral health organization (an arrangement known as a “carve-out”), this could alter their contact with prescribers and use of SGAs as compared to arrangements in which mental health and physical health services are either coordinated through a single managed care organization (“integrated”) or reimbursed using traditional fee-for-service payment. In a recently published article in Psychiatric Services, we assess the relationship between SGA use among vulnerable children and mental health services organization in 82 diverse counties.

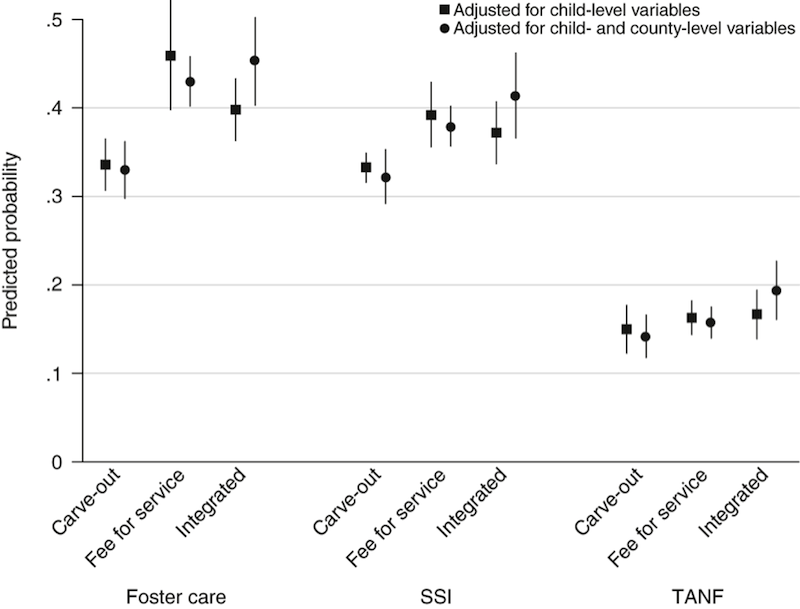

To understand more about how counties organized their mental health benefits, members of our study team, led by Dr. David Rubin, conducted a comprehensive review of policy documents from the 82 counties and categorized those counties based on method of reimbursement and division of administrative responsibility. Within these counties, we focused on the medical claims of roughly half a million children collected from multiple years who were taking stimulant medications (a population of children likely to be at risk of SGA use). Our study reveals significant variation in use of SGAs by county organizational structure, with use lowest in counties with a carved-out benefit design. For example, after adjusting for potential confounders, we found that SGA use was 31% lower among foster youth residing in counties with a carve-out compared to fee-for-service counties, and the difference was comparably large between children residing in carved-out versus integrated counties. The figure below reveals these key differences in the probability of SGA use by eligibility group of the child

Predicted probability of second-generation antipsychotic use among stimulant-using youths, by Medicaid eligibility group and county organizational structure. Vertical lines indicate confidence intervals. SSI, Supplemental Security Income; TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. (Note that SSI is a program for disabled children and TANF is a pathway into Medicaid based on low-income without a qualifying disability; also note that in one set of models we statistically adjusted for both child and county-level variables, but these results were quite similar).

What accounts for these dramatic differences between carve-outs and other organizational models? We hypothesize that there may be differences in how the care of high-need children is managed in different systems. While carve-outs have raised concerns about restricting access to some groups of children, they may also provide some tools that improve case management or prevent hospitalizations – a setting where SGA use is commonly initiated. Another possibility is that carve-outs may exert greater pressure over the network of providers – for example by following up with prescribers who administer the highest cost medications. We hope that these, and other, potential hypotheses spur further research on system organization, especially studies that use longitudinal data and other measures of service use to track the trajectories of children with elevated need for care before and after the implementation of these policies.

Benefit design should be considered as one potential element in state and national quality improvement efforts for children’s mental health currently underway. Support for increasing funding for children’s mental health services recognizes that these services are often fragmented, and that access to alternatives therapies, including family-focused interventions and psychotherapy, are underutilized. Developing systems of care that simultaneously provide oversight of psychiatric medications children with complex needs, while simultaneously promoting access for those children who need services will require new investments in care coordination and greater availability of evidence-based treatments – medication or otherwise.